The appointments of Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP’s plush Toronto office digs are familiar on Bay Street. There’s the collection of contemporary Canadian art and the lofty view that renders Toronto’s skyline in miniature. Yet it’s the appointments behind the top desks at this firm that differentiate it from its peers. You see, at Osler, women run the game.

When lawyer and business development director Jodi Kovitz counts off women at the top of her firm, she runs out of fingers. The chief executive. Managing partners in Calgary and Ottawa. The chief operating officer and the chief client officer. Heads of litigation, tax, real estate, research, and on and on: all women. “We are committed to women comprising 30 percent of our teams, and we meet that objective as often as possible,” she says. Having women in senior roles is so common, it’s hardly a novelty. As Dale Ponder, the chief executive and national managing partner of Osler puts it, “It really is part of our DNA.”

And while Osler holds itself to metrics and boasts for-women initiatives, really the most impressive thing — the true good news — is that its office culture supports and sponsors women. And elsewhere on Bay Street, this cultural shift is happening as well.

Private practice is not easy on female lawyers, which statistics underscore. Only 35 percent of lawyers in private practice are women. And at the partnership level, women comprise merely 20 percent. In their first five years in private practice, women are nearly 50 percent more likely to leave than their male counterparts.

Gender parity is elusive. Retention is a serious, costly issue. All it can take is a family crisis, a childcare implosion or an inflexible boss to catapult a career into the hinterlands. “Generally, law as a profession doesn’t have the best reputation when it comes to the support of women,” says Ashleigh Frankel, a lawyer and co-founder of Click & Co., a consulting and career coaching company that, among other things, transitions female lawyers back to the workplace. “At most firms, you come to work and you are a lawyer. Anything you need to juggle your life is left outside of firm life,” she says. “But the landscape is starting to change.”

Women at the top

Optics count, and for women on Bay Street, just seeing other women at the top inspires. This was something heard from both established luminaries at Osler and rising stars like senior associate and Ironman triathlete Lauren Tomasich. “There’s this tradition here of women leaders who are confident, smart and charismatic,” she says. Joyce Bernasek, an “Oslerite” since 2002 and a partner, agrees. “Having women in leadership roles sends the message to me that the firm values women,” she says, working from home when we spoke, to attend her daughter’s school recital. Positive role models beget positive role models.

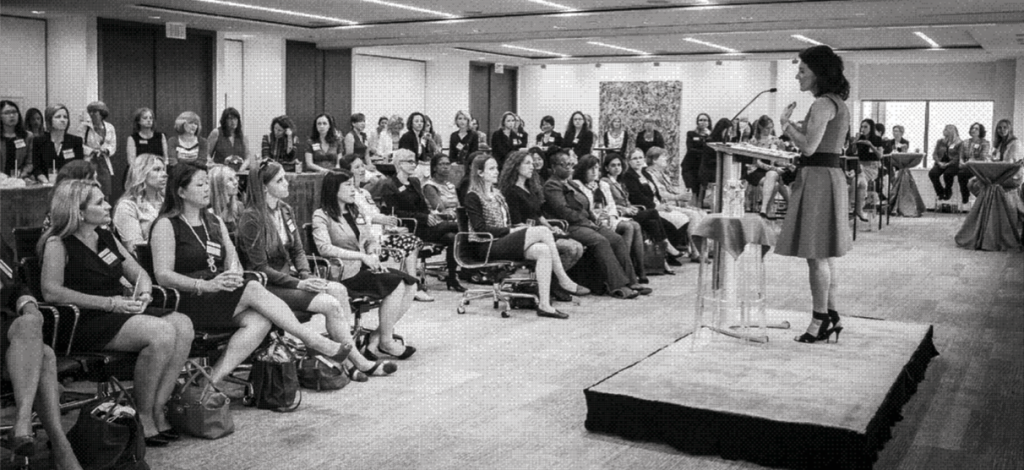

Osler managing partner Dale Ponder addresses an audience of female lawyers and clients at the firm’s annual Women’s Day event

Osler takes an active role in retaining its female associates, with initiatives like the maternity-leave buddy-program that matches partners (both male and female) with associates on leave.

Despite all the good news for women at the firm, Osler is not at gender parity — only 118 of the 288 lawyers at its Toronto office are women. But Bay Street firms are inching closer. As of 2014, Lerners LLP is one of the first major firms in Canada to reach a 50/50 split. “It happened organically,” says Lisa Munro, executive committee member and partner. “I attribute that to the leadership in our firm in the 1990s — it really set the tone,” Munroe recalls. “Janet Stewart was our managing partner. She had good soft management skills and also ran a profitable practice. She was what everyone wanted to be.”

Women have always aspired to leadership roles, but what’s improved about the situation today is that seeing women in leadership roles is not just an aspiration, says Munro. “It’s a law-firm and societal expectation.”

Sponsorship from men

Men make up the majority of warm bodies in private practice, so they need to sponsor women — a notion that is finally starting to suffuse through Bay Street’s corridors. Deborah Glatter, lawyer and professional development director at Cassels Brock & Blackwell LLP, held a seminar last year titled, “Sponsorship: What Powerful Male Leaders Need to Know.”AlthoughCassels has upwards of 25 percent female equity partners,“we’d like that to be higher,” she says.

Her seminar ran top men (and women) at the firm through a Harvard quiz on implicit bias; a talk from Beatrix Dart, an associate dean at the Rotman School of Management; and a roundtable discussion. “One of the powerful men sitting at the table said, ‘Raise your hand if you were sponsored by a man,’ and all of them, including the powerful women, raised their hands,” says Glatter. Usually men have sponsored men, she adds, and that hasn’t helped retention. “Women are just as ambitious as men, but they’re not stupid. They see the male associate being brought along with the male partner and work starts flowing to the associate. Why would you work as hard when your path to success is not clear?”

Her message is getting through, and she proudly reports that recently a partner said he is going to “pound the table” to have his female sponsoree become partner. “The more women become partners here, the more clear it is to female associates they will become partner. They’re not going to stick around if those opportunities aren’t given to them.”

Indeed, at Osler, Ponder says men have been crucial to promoting women at the firm. “Our women have had strong male voices at our firm who have championed their abilities,” she says. “This truth is an important part of our culture and it was also true of my own personal experience.”

Fostering retention

Let’s be honest here: when the loaded diaper hits the fan on the homefront, women clean up. A family crisis, the strain that comes with having children, pressure to truncate maternity leave — all of these contribute to women dropping out of private practice. This was especially true in decades past. “In my experience, women used to quit after having a kid or two,” recalls Tracy Sandler, Osler’s energetic and polished partner who has been at the firm since 1991 and now sits on the executive committee. Sandler took eight-month maternity leaves back when six months was the standard, and made partner while on her second maternity leave. And moves like that set a mom-supportive cultural tone that others benefit from. Mary Paterson, a newly minted litigation partner at Osler with a calm yet commanding presence, took a year of maternity leave as an associate, a relative rarity on Bay Street. Consequently, she pays it forward. “I tell women to take the year. It was the best decision I made,” Paterson says.

Formally, some firms offer in-house support for lawyers with families. And consulting companies like Frankel’s Click & Co. offer seminars and coaching packages, such as “Mat-Leave-to-Meeting,” that help women navigate this transition. But at a macro level, “woman friendly” firms like Lerners or Osler aren’t doing anything gender-targeted so much as managing with humanity: you’re a person, not a lawyer-bot, you will weather shitstorms, and they will support you.

And yet, the reality is that Bay Street does not amply support working parents. Not like more progressive sectors such as tech — your Googles and Facebooks — where some employers offer on-site daycares or subsidies for caregivers. The rigours of the partnership track remain unchanged. Nannies that can accommodate early and late hours are a reality for working moms, as is a “supportive and forgiving family,” according to Sandler.

“They told me: ‘We need to see a woman in the corner office!’”

Lisa Munro

Partner at Lerners

This shrug-and-deal-with-it approach is, for now, the norm. No one really seems to have cracked the code for making law firm life much easier on parents, though lawyers aren’t without ideas. “Firms could improve a bit on flexibility and have a more set arrangement where you can work from home,” says Bernasek, in the financial services group at Osler. “Though the commercial reality is that you should be showing up to work on most days, that could improve. If we’re not in our office it doesn’t mean we’re not working.”

At Lerners, Munro remembers an excellent female lawyer who came in to resign when she hit a work-life impasse. “I asked her, ‘Do you like practising law here?’ She said yes. ‘Then I’m not going to let you resign.’” Munro asked her, “Have you thought of a leave of absence?” The lawyer took a leave and now she is back at work and has advanced in her career. “Years go by in a flash,” Munro says, “so when you’re making a long-term investment in people, we think, Let’s make it work.”

The next generation

One of the best pieces of news for women on Bay Street is that, as a new generation of both clients and lawyers rise through the ranks, they bring with them enlightened Millennial attitudes. The old boys’ club, with golf rounds and steakhouses, hasn’t totally gone the way of the Rolodex, but today’s young lawyers of both genders expect equality.

“Men of today’s generation grew up with women in leadership roles,” says Mary Abbott, a partner at Osler in the corporate group. “They think, Of course there will be women at the top.”

Women in law also assert themselves, unlike their cohort of a decade ago. “I was at my desk minding my own business,” says Munro, “and some younger female lawyers came into my office and said, ‘There’s a vacant corner office. You need to go into it.’ They told me: ‘We need to see a woman in the corner office!’” Looking back, the event was particularly meaningful. “It educated me too, in terms of what younger people want to see in the firm.”

There’s a new generation of female lawyers gunning for the top spots on Bay Street — women who are ready, to use Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg’s groundbreaking term, to lean in. And more than ever before, Bay Street is actually ready for them.

Change doesn’t just happen

Becoming a standard-bearer of the Bay Street women’s movement doesn’t happen overnight. Both Osler and Lerners have a long history of women ascending to the upper ranks of partnership. Here are three standout examples of women who helped pave the way.

Justice Bertha Wilson

Justice Bertha Wilson

At Osler from 1959–75

When she applied to law school at Dalhousie University in the mid-1950s, the dean of law replied: “Why don’t you just go home and take up crocheting?” Well, she didn’t take his counsel. Within two decades, Wilson had made partner at Osler (the first woman to do so in Big Law). Then, in 1982, she was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada — the first woman in Canadian history.

Janet Stewart

Janet Stewart

At Lerners from 1972–present

Back in the 1980s, Lerners was a small place. Based in London, Ont., the firm housed about 25 lawyers. Then Janet Stewart came along. During her reign as managing partner, from 1991 to 2007, the firm quadrupled in size, reaching more than 100 lawyers.

Jean Fraser

Jean Fraser

At Osler from 1993–2015

Before there was Dale Ponder, the current top lawyer at Osler, there was Jean Fraser — who became the national managing partner at the firm in 1999, cementing Osler’s reputation for promoting women. In fact, she’s always been a trailblazer. In Fraser’s first year of practice at Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP, she convinced her firm to adopt its initial maternity leave policy.

This story is part our series on how Bay Street firms are getting better, from our Fall 2015 issue.

This story is part our series on how Bay Street firms are getting better, from our Fall 2015 issue.

Concept photography by Chris Thomaidis.