I can’t tell you how many times I’ve met a charming and eccentric winemaker — they are nearly all charming and eccentric — who, after being complimented on the wine, gestures expansively towards his vineyard and says, “I do nothing but let the fruit speak for itself.” Or: “The vineyard is the true winemaker. My job is to stand out of the way.”

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve met a charming and eccentric winemaker — they are nearly all charming and eccentric — who, after being complimented on the wine, gestures expansively towards his vineyard and says, “I do nothing but let the fruit speak for itself.” Or: “The vineyard is the true winemaker. My job is to stand out of the way.”

The notion that wine is nothing but a pure expression of the land is romantic hokum. A huge part of the taste of most fine red wines (and many whites) originates not with the vineyard or the vintage, but with something much more prosaic: a wood shop. Great wines wouldn’t exist without cooperages, the more-or-less traditional workshops where craftsmen bend oak staves into barrels. Wine can be aged in barrel for anywhere from a few months to several years, leading to a complex series of chemical changes which affects every grape in different ways.

Knowing something about how barrels are made is a key to understanding why

your favourite wine tastes the way it does. If the staves are fashioned by splitting the wood by hand with a chisel, the barrel imparts less astringency (or tannin) into the wine than a barrel with sawn staves. Also, the staves are often heated over a fire so that they can be bent. A lightly toasted barrel allows the sappy, herbal flavours of the oak to seep into the wine. A deep toast, on the other hand, infuses the wine with notes of coffee and smoke. Using one or the other is a matter of taste.

But when you meet a charming and eccentric winemaker, it’s unlikely he’ll explain any of this. It may be because so many bad wines are saturated with crude, woody flavours thanks to their time in a barrel. Or perhaps it’s a matter of pride: every winemaker I’ve ever met spends time in his vineyard, but I’ve never known one who makes his own barrels. So while the artistry of the cooper remains shrouded in mystery, so does the foolproof recipe for a perfectly aged wine.

Into the Short Cellar

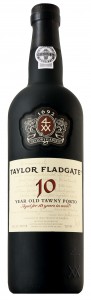

Taylor Fladgate 10 Year Old Tawny Port

Taylor Fladgate 10 Year Old Tawny Port

$34.95, Portugal, Vintages #121749

The best way to understand how oak transforms wine is to sample a tawny port. Tawnies are named for their bronze hue, which comes from being barrel-aged for 10 years. The Taylor Fladgate is a particularly tantalizing specimen, filled with sweet flavours of pecan, butterscotch and spice balanced with ripe fruit. 92/100

![]() 13th Street 2010 Sandstone Reserve Chardonnay

13th Street 2010 Sandstone Reserve Chardonnay

$34.95, Ontario VQA, Vintages #230862

This luxurious Chardonnay is a superb example of how artistically applied oak creates complexity. Brand-new barrels give stronger flavours than barrels that have already seen a year or two of use. 13th Street aged the excellent fruit of 2010 in French barrels of various ages, creating a layered texture in the final product. 90/100

Roll out the barrel

Along with staves and toasting, the origin of the oak affects what a barrel does to your wine

Staves of French oak are usually hand-split. The wood has a subtle and spicy flavour that doesn’t overwhelm delicate wines. However, it’s so expensive (almost $1,000 per barrel) that it can seriously inflate the cost of a wine.

Staves of French oak are usually hand-split. The wood has a subtle and spicy flavour that doesn’t overwhelm delicate wines. However, it’s so expensive (almost $1,000 per barrel) that it can seriously inflate the cost of a wine.

American oak is a different species with a more assertive profile — it adds sweet notes of vanilla and coconut, but more woody tannin. Loading American oak into a robust grape like Shiraz can create a truly opulent wine.

American oak is a different species with a more assertive profile — it adds sweet notes of vanilla and coconut, but more woody tannin. Loading American oak into a robust grape like Shiraz can create a truly opulent wine.

Eastern European oak provides a middle path that moderates the sweetness of American and the silkiness of French. It’s actually the same species as French oak, but cheaper, making it an attractive alternative

Eastern European oak provides a middle path that moderates the sweetness of American and the silkiness of French. It’s actually the same species as French oak, but cheaper, making it an attractive alternative

Matthew Sullivan is a civil litigator in Toronto. Email matthew@lawandstyle.beta-site.ca.

Image: Cole Vineyard via iStockphoto