From his understated offices in a tower at Yonge and St. Clair — decorated with a dusty tropical plant in reception and not much art — Kevin West talks about the eureka moment that later inspired him to co-found the firm SkyLaw LLP here, beyond the pale of downtown. He was pulling an all-nighter 12 years ago, researching a tiny but critical point required to finalize a corporate deal. The former Dalhousie dean’s lister and Supreme Court clerk’s ability to conduct orderly, no-stone-unturned legal research had helped him earn his position at top-tier Wall Street firm Sullivan & Cromwell LLP.

“Midway through that process in the early hours of the morning I thought, ‘You know, someone out there knows the answer to this. This could be 10 minutes of their time, but instead it’s taken me hours. Why should the client pay for that?’”

So when West launched SkyLaw last fall with former Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg LLP colleague Michael Lee, they made efficiency their watchword. They cherry-pick people from various firms to assist in a dream team tailor-made for each deal. On a tech deal, for instance, they call on a strategy talk with the head of an IP group at a big downtown firm and get tech-related due diligence from one of the patent-law boutiques. “It’s about matching the right work to the right type and level of person,” Lee says.

– – –

The approach and partnership worked: a week after launch, a Sullivan & Cromwell partner sent a major corporate merger their way.

Instead of billing for hours, they can bill on a transactional basis, or with a “success fee.” Their bare-bones office has no secretaries, just a practice manager. For due diligence and corporate searches, they use one full-time and two part-time, senior law clerks. To make client pitches look sleek, they frequently call on a graphic designer. They rely on their MacBooks, iPads and iPhones, loaded with cutting edge software such as Liquid Practice and Board Suite. “With the new technologies, we can provide many of the support systems that the traditional firms have,” West says.

West and Lee met in 2009 while working at Davies. Lee’s resumé includes the A-list American firm White & Case LLP in its London, U.K., office and McCarthy Tétrault LLP, where he helped grow the firm’s practice advising Chinese investors in Canada. The seemingly all-biz Lee actually sings opera in his spare time, while the congenial West is his daughter’s encouraging hockey coach.

With this launch, West and Lee have joined a growing cluster of U.S. and Canadian lawyers who have been influenced by British scholar Richard Susskind’s 2008 work, The End of Lawyers?, and have been inspired to reinvent the practice of law. They’re not the usual malcontents who leave — or are asked to leave — the downtown firms, and always look back in anger. These blue-chip lawyers are not constitutionally boat-rockers, but they share the same intuition about the longstanding traditions of the downtown practice: there must be a better way. A more efficient, cost-effective way of servicing client needs. And for lawyers, a new approach to the work.

Before founding SkyLaw, West consulted with former Supreme Court justice Ian Binnie, whom he’d clerked for. “Kevin is very careful,” Binnie says, “and he’d done his research. If he saw a hole in the market, then there was one — there is one.”

SkyLaw is part of a trend we might call The Firm 2.0. Because this new approach may, soon enough, make the plush offices of the old-line firms — with their banks of cubiclebound secretaries, libraries filled with leatherbound texts and wood-paneled conference rooms lined with Ed Burtynsky photos — seem as retro as the ad agency in Mad Men.

– – –

The local revolutionaries have one international model in mind: Axiom. It was cofounded by young attorney Mark Harris, who had been working as an associate at the white-shoe New York firm Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP. Early one year, after a busy couple of months at work, Harris realized he’d already billed his annual salary. For the rest of the year he’d be working to pay for office overhead and partner draws.

He didn’t like the math, so he and serial entrepreneur Alec Guettel launched a firm in 2000 with a minimal office, no partners and lawyers who worked mainly at client offices, getting paid a higher proportion of their billings.

They brought in top lawyers and clients who were tired of the old system. “We knew a lot of incredibly talented, incredibly unhappy attorneys, working incredibly hard. For them, partnership is not the brass ring that it once was,” Guettel says. “On the other side, we saw a lot of clients who felt that it wasn’t an efficient system, and that getting top-tier legal advice was too expensive.”

Following project-management-style efficiency, Axiom delegates work to its 11 offices and four delivery centres worldwide. The firm now has over 600 lawyers, about half of them female. “This is a model that appeals to a lot of women,” Guettel says. With barebones offices in New York, London and San Francisco, Axiom’s revenues have grown from $55 million in 2008 to more than $100 million last year. This serious money — along with a client list that includes the likes of eBay, Thomson Reuters and Cisco — is making the industry take notice. And pay the ultimate compliment of imitation.

– – –

Rubsun Ho (ex of Stikeman Elliott LLP) and Joe Milstone (ex of Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP) were among the earliest adopters of the model in Toronto. Their alt-firm Cognition LLP occupies a funky but no-frills space that takes up half the floor of an old garmentdistrict building just west of the downtown core. The two met when they were neighbours in the Annex, and they have been providing workaday corporate advice by embedding their lawyers at clients’ offices since 2005. The feel in the office is über-casual, with Milstone’s son, on school break, watching European football on a big-screen next to an Ikea shelf housing legal texts, many lying aslant.

“We both had been at firms and in-house at major companies. We saw a way of servicing clients that was somewhere between having someone permanently in-house and retaining an outside firm,” says Milstone. “When you need us, we come; when you don’t, we go away.” At first, Cognition worked with start-ups and mid-sized operations, but its client list now includes Rogers Communications, Sun Microsystems and Siemens Canada.

Similarly, ebullient corporate lawyer Peter Carayiannis left Gowling Lafleur Henderson LLP in 2004 to work as general counsel, not for one company, but five, sometimes six, separate ones. “My clients were all companies that had recurring, complex, sophisticated legal needs, but often not enough work for a full-time counsel, and the fees for legal services downtown seemed too high to them.” He has just launched Conduit Law Professional Corporation and is bringing other topnotch lawyers (mainly five-to-10-year calls) along for the ride.

Carayiannis says every year he’s made more money than he did as a senior associate at Gowlings. No surprise, since he has almost no overhead, and gets to keep all his billings. Cognition’s lawyers, when they put in fulltime hours, can earn between $175,000 and $250,000 — what a vice-president of legal at a major corporation might earn, if not what similar calls would pull in downtown.

It’s not just the final tally, but the logic of the money that appeals. “I remember staring out my 55th floor office at Lake Ontario after I found out my billing rate was $250 per hour,” recalls Ho of his Bay Street days. “I mentally did the math. I’m only getting $40 an hour — that difference has to be spent on something.”

What else motivates top-tier lawyers to forgo the perks of a well-appointed office to become secretary-less legal nomads? “Control,” says Milstone. “Most of our people work full-time, but they have control over that. If they have a period where they need to slow down — a sick parent, child care duties, a book to write — they can.”

Carayiannis says he still works hard, but he’s more in control of his schedule, enabling him to sometimes pick up or drop off his young son. “And I’ve never worked a weekend since starting this,” he brags.

The model has appeal both for lawyers and clients. But at first, it’s a tough sell. All these lawyers tell stories of meetings with initially skeptical clients used to getting legal advice from name-brand firms. Ho quotes the old business adage: “No one ever got fired for hiring IBM.”

But things turn around quickly once clients get a taste. “We’re like crack,” Milstone says. “Once you’ve tried it….” He continues, “When you’re the lawyer at the client’s offices, you understand better what they’re dealing with and you never take a memo-laden, coveryour- ass kind of approach to the advice you give.” Clients used to endlessly piled-on bills with extra costs and multiple lawyers on one file appreciate the simpler billing practices of these alt firms. “Especially after the downturn, clients have been looking for significant savings,” says Milstone.

At SkyLaw, the efficiency mantra has huge client appeal. “We always want the most efficient person, the person who can do it the quickest and best. Often, through our networks, we know who that person is, or can find out,” says West. “We can pass along the savings of getting things done efficiently, without a lot of overhead, to our clients.”

– – –

This emerging model does have its detractors. The Canadian firms are relatively new arrivals in the market and it’s not yet clear whether they’ll draw significant business away from older firms. So there’s not much local trashtalking going on — yet. But in a post headlined “Temporary Attorney: The Sweatshop Edition,” one legal blogger in the U.S. dismissed Axiom as a “temp agency masquerading as something new, so cool and so different…. If you love kissing ass and love working in a SoHo loft with a bunch of loser wannabes, then Axiom is the place for you!”

Guettel’s not fazed by the criticism. “By any metric you can use — the credentials of our lawyers, our revenues, the clients — we’re succeeding. We’re getting 50 lawyers applying for each open spot. The tide runs in our direction.”

Indeed, from a certain angle, this shift towards a new type of firm does look inexorable. It’s driven by powerful forces: the new technologies that are revolutionizing many traditional businesses (not just law); postdownturn clients who want lower legal bills and advice tailor-made to their business needs; and accomplished young lawyers who work hard but also want to enjoy full outside lives.

Carayiannis turns pensive post-interview, while walking on the fringes of the downtown Toronto core and looking at the skyline. “All those towers, with all the advances in technology. The firms are still renting the same space in all those towers. It just seems, well, strange.”

Tech innovations are helping former Bay Streeters to reinvent private practice. And now entrepreneurs with a law background are using the web to help people locate the right legal professional.

Jeffrey Fung, former Queen’s Law Students’ Society president and McMillan LLP associate, started mylawbid.com last summer after he and his family-lawyer wife struggled to find a real estate lawyer when buying a condo in 2009. The site enables people, organizations and businesses to post (for free) their legal problems on the site, and to have lawyers respond with thoughts and action plans. The site is soon to move out of beta, so lawyers will pay a fee to get their responses to the prospective clients. The value-adds: Fung’s site helps lay people aptly describe their legal problems, and can give featured lawyers a greater presence on the web.

Jeffrey Fung, former Queen’s Law Students’ Society president and McMillan LLP associate, started mylawbid.com last summer after he and his family-lawyer wife struggled to find a real estate lawyer when buying a condo in 2009. The site enables people, organizations and businesses to post (for free) their legal problems on the site, and to have lawyers respond with thoughts and action plans. The site is soon to move out of beta, so lawyers will pay a fee to get their responses to the prospective clients. The value-adds: Fung’s site helps lay people aptly describe their legal problems, and can give featured lawyers a greater presence on the web.

Vancouver lawyer Shane Coblin describes his new site legallinkup.com as eHarmony meets Priceline — wouldbe clients get to scope out prospective lawyers via the site and then get quotes on a given job. Coblin, a corporate law partner at Kornfeld Mackoff Silber LLP and also the founder of the humour site whostheass.com, had several tech entrepreneur friends with simple legal needs, who had no real sense of how to find a competitively priced lawyer. “With other goods and services, they’re used to this approach, so we thought it would work.”

Vancouver lawyer Shane Coblin describes his new site legallinkup.com as eHarmony meets Priceline — wouldbe clients get to scope out prospective lawyers via the site and then get quotes on a given job. Coblin, a corporate law partner at Kornfeld Mackoff Silber LLP and also the founder of the humour site whostheass.com, had several tech entrepreneur friends with simple legal needs, who had no real sense of how to find a competitively priced lawyer. “With other goods and services, they’re used to this approach, so we thought it would work.”

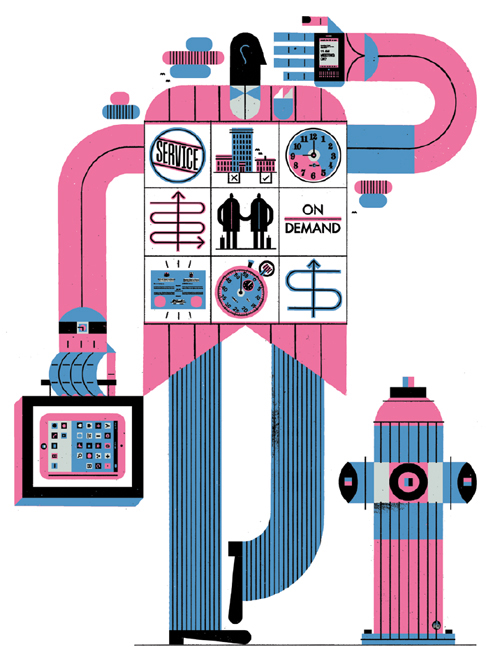

Illustration by Raymond Biesinger