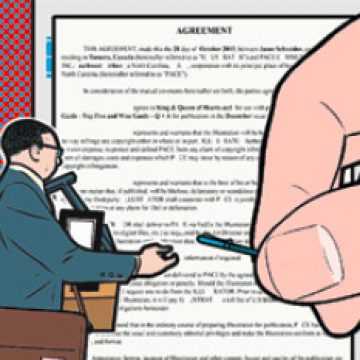

I know you’re upset that you were let go. But we’ve made progress and now you’ve got a decent offer on the table. But there’s just one thing: you can’t ever say anything negative about your employer. Not ever. Yes, I know that you put up with a lot in your 25 years. But once you sign this, you can’t talk about any of the bad stuff. And not just about the company, but any of its employees — all 125,000 of them. Oh, and I really should add past employees, directors and agents as well. And nothing negative about the company’s foreign affiliates either; so no mention of sweatshops overseas or contaminated groundwater. And just one final thing: you can’t tell your kids, your grandkids and … well, you get the picture.

This is one of the most perplexing new trends in employment law today — one that infringes on an employee’s basic freedom of expression. When employees are terminated, they routinely come to settlements with their employers that may be fair with respect to reasonable notice, but there’s a twist. Snuck into the release prepared by the employer’s counsel is a so-called non-disparagement clause that forbids any kind of badmouthing of the company, in perpetuity.

After negotiating with their employers to reach financial settlements they can live with, employees are faced with a new challenge: sign the release and stay quiet forever or refuse to sign and litigate. Over what? The freedom to bitch about the lousy pay and the boss from hell? The situation is not unlike that scene in Lord of the Rings where Gandalf appears to have slain the Balrog in the Mines of Moria, only to have the beast unfurl its fiery whip at the last possible moment and drag poor Gandalf into the darkness below. As Boromir laments, “What is this new devilry?”

Employers have figured out that in exchange for giving more than the absolute minimum required by employment standards legislation, people will often sign. Such clauses usually include provisions requiring the return of all payments should a breach of the covenant occur. Serious stuff.

Some of my best clients are employers. I understand that there are times when non-disparagement clauses make sense. When the dispute involves the employee’s allegations of impropriety by the employer or co-workers, the employer is unlikely to settle the matter without some assurance that the employee will not share the tale — particularly over social media where such stories can quickly go viral and have a real impact on a brand. But these clauses are showing up in routine terminations without cause, where the only dispute is the reasonable notice period.

Given the disparity in bargaining power between employer and employee, particularly at the point of termination, the law needs to declare non-disparagement clauses prima facie unenforceable, absent compelling circumstances. Employment law has often held post-employment non-competition clauses to be unenforceable based on the inefficacy of restraint of trade, so why should an employee’s freedom of expression be less important?

What it really comes down to is the impact of work on our lives. The Supreme Court has held that “work is one of the most fundamental aspects in a person’s life… A person’s employment is an essential component of his or her sense of identity, self-worth and emotional wellbeing.” Losing a job is tough. Losing the ability to ever speak freely about the job adds insult to injury.

You can also hear our podcast featuring a discussion with Andrew Pinto about his article.

Andrew Pinto is a civil litigator in Toronto with Pinto Wray James LLP and a Lord of the Rings fan.

Illustration by Jason Schneider