When Precedent’s first issue came out, a decade ago, less than 12 percent of lawyers in Ontario identified as racialized. But since then, that figure has climbed to 19 percent. For this special anniversary edition of the magazine, we sought out three racialized lawyers — whom we’ve profiled in these pages before — and asked them to reflect on how the profession has changed.

Their message: don’t get too excited by the numbers. For one thing, lawyers in Ontario remain less diverse than the province’s general population, which is 26 percent racialized. And, as research from the Law Society of Upper Canada shows, discrimination — ranging from unspoken bias to outright harassment — is a reality for many racialized lawyers. What follows are three status reports on the battle for racial equality in law.

Ranjan Agarwal

Ranjan Agarwal

Partner, Bennett Jones LLP

First appearance in Precedent: Summer 2012

Eighteen months ago, Ranjan Agarwal, a partner at Bennett Jones LLP, was preparing an RFP. The potential client said it wanted to hire a diverse legal team, so Agarwal assembled a lineup with both experience and diversity that no firm could match. He told a colleague, “We’ve got this.”

Then the client picked a team of five white, male lawyers — a harsh reminder that some clients merely pay lip service to diversity. Until clients refuse to hire non-diverse teams, explains Agarwal, firms won’t feel genuine pressure to advance racialized and female lawyers. In his view, this won’t happen until clients grasp that diversity is good for the bottom line. And, indeed, it is: a 2015 McKinsey study found that racially diverse companies outperform industry norms by 35 percent. “At some point, people will realize they could be making more money,” says Agarwal. “And money is the one language that everyone in business speaks.”

Agarwal, a past president of the South Asian Bar Association, says he’s never personally experienced overt racism in his career. But he agrees that to succeed as a racialized lawyer requires (sadly) a balancing act. He often takes phone calls from Sikh students wondering if they should shave their beards before interviews or from Muslim students asking if they should whitewash their resumés and remove evidence of their religious affiliations. And his wife may roll her eyes when he talks to colleagues about going to the cottage or having kids in hockey — two Ontario-centric experiences that Agarwal, a son of Indian immigrants, knows little about — but he sees such banter as a necessary step toward the ultimate goal: moving up the ranks, so there’s one more diverse lawyer in an influential role. “Change will only come,” he says, “as we move into places of power.”

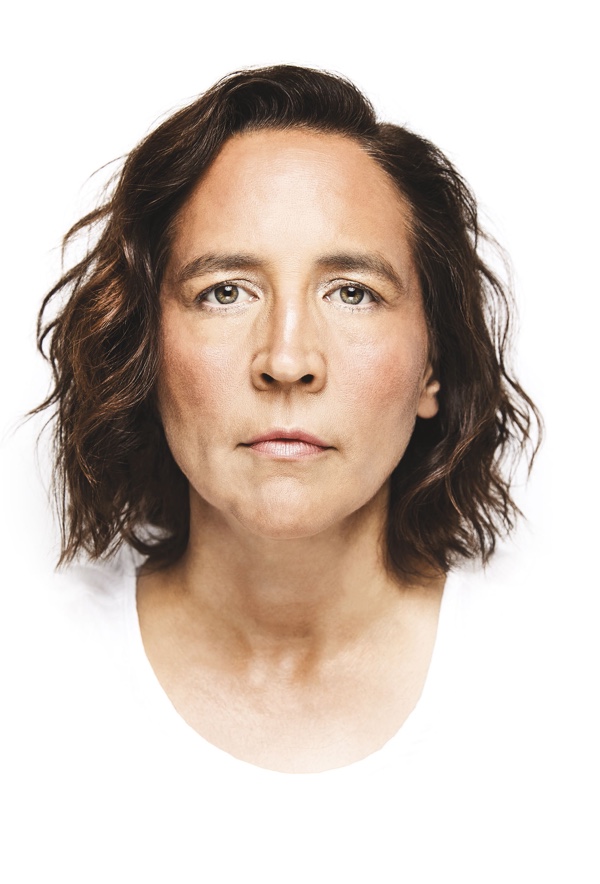

Katherine Hensel

Katherine Hensel

Principal, Hensel Barristers

First appearance in Precedent: Winter 2012

Katherine Hensel is used to being an outlier. When she was called to the bar, in 2003, she was both one of the few Indigenous women and single mothers on Bay Street. She started her career at McCarthy Tétrault LLP and later moved to Stockwoods LLP. These days, the Secwepemc lawyer runs Hensel Barristers, a firm dedicated to Indigenous litigation.

In the courtroom, where Hensel handles all manner of civil and criminal trials, casual racism is common. “There are times,” she says, “when Indigenous lawyers show up and the court staff will ask, ‘Do you need to see duty counsel?’” This has happened to Hensel. When she hears such comments, she speaks up, but knows that not everyone does.

The justice system itself can also be deeply ignorant. Hensel often represents survivors of residential schools, who are making claims against the government. And in court, she still has to educate judges and opposing counsel of the consequences — intergenerational trauma, for instance — of one of Canada’s darkest moments. Thanks to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, she can simply hand its final report to the judge. But it still means that she has to deliver a history lesson to the court. “Every case that comes up is an opportunity for me to educate people,” says Hensel. “But I don’t want to have to educate people. I want access to justice for my clients.”

Hensel would love to hire Indigenous lawyers and students, but, at the moment, doesn’t have one. Part of the problem is that litigation runs counter to the consensus-based decision-making common in many Indigenous communities, which drives young Indigenous lawyers away from the area. “Indigenous litigators are thin on the ground,” says Hensel. “But I’m actively looking.”

Paul Jonathan Saguil

Paul Jonathan Saguil

Associate VP, TD Bank

First appearance in Precedent: Summer 2015

Paul Jonathan Saguil never asked to be a poster child for diversity. But in 2008, as a first-year associate at Stockwoods LLP, he decided to be open about the fact that he’s gay. Because he was so outspoken, the requests — first, to speak on diversity panels and, later, to sit on boards — flooded in. “I just kept saying yes,” says the associate vice-president at TD Bank. Fast-forward 10 years and Saguil, who is Filipino, holds executive positions on — ready for this? — the Law Society’s Equity Advisory Group, Out on Bay Street, and the CBA’s Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Forum. And he previously held positions on the Federation of Asian Canadian Lawyers and Pride Toronto.

Over the past decade, the 35-year-old has seen tangible change. Both law firms and in-house departments now hire diversity officers, host panels and throw cocktail parties for Pride Week.

But Saguil fears that such initiatives have started to outlive their usefulness: he often sees the exact same people showing up at diversity events. “Sometimes it’s frustrating,” he says. “I look around the room and think, Are we just in an echo chamber?”

Saguil’s tireless dedication to equality has also taken a personal toll: a recent relationship ended, in part, because of how many hours he put into the cause. He wonders if his relationships would be stronger if he took a step back.

But until he stops getting middle-of-the-night messages on LinkedIn from strangers asking for help because a colleague has made a pejorative remark, his work isn’t over.

One thing, though, is certain: the increase in the number of racialized lawyers has forced the profession to take their concerns seriously: “We can’t be silenced anymore.”

This story is from our 10th anniversary issue, published in Fall 2017.

This story is from our 10th anniversary issue, published in Fall 2017.

Photography by Luis Mora; Hair and makeup by Michelle Calleja