No one ever said articling was perfect. After all, horror stories of negligent principals often work their way through the grapevine. But conventional wisdom maintains that articling is the best way to give students hands-on experience. That theory has now been put to the test.

In 2014, Ontario piloted a new way to train lawyers. In the past two years, close to 500 law grads completed the Law Practice Program (taught in English at Ryerson and in French at the University of Ottawa) instead of articling. The program consists of four months of mostly online coursework and a four-month work placement.

In September, the LPP sat on a razor’s edge, as the Law Society of Upper Canada considered scrapping it. But backlash from the profession persuaded the benchers to keep it for at least two more years. How did the LPP earn such loyalty? Because, on several fronts, it’s better than articling. Here’s the proof. After the 2015–2016 licensing period, the Law Society commissioned a survey of law grads who went through the LPP and the articling system (which itself trains about 1,400 students a year). And the findings shine a light on some core problems with the articling process. Here are three of them.

The articling system is too reliant on Big Law

The largest firms have always played an outsized role in articling. In the most recent articling period, as this chart shows, 22 percent of all articling students worked at firms with more than 200 lawyers. This is partly a good thing. The juggernauts of Bay Street pay excellent salaries and train their student cohorts with care.

But there’s a downside: most lawyers don’t work in Big Law. In Ontario, a whopping 81 percent of private-practice lawyers work at firms with fewer than 50 lawyers. Out of roughly 38,000 lawyers in the province, almost a quarter are sole practitioners and 12 percent work in-house. If articling is supposed to represent what students will actually do, it doesn’t come close. The LPP, by contrast, gets way closer: in its second year, 18 percent of all work placements took place at in-house departments and 17 percent with solo lawyers.

A breakdown of the types of law offices that took on articling students compared with LPP students in 2015:

Employer |

Percentage of articling students hired |

Percentage of LPP students hired |

|---|---|---|

| NGO | 1 | 3 |

| Other | 4 | 2 |

| Crown’s office | 3 | 1 |

| Education | <1 | 3 |

| Government or public agency | 13 | 12 |

| In-house | 2 | 18 |

| Legal clinic | 2 | 6 |

| Sole practitioner | 7 | 17 |

| Small firm (2-5 lawyers) | 9 | 31 |

| Mid-size firm (6-199 lawyers) | 37 | 6 |

| Large firm (200+ lawyers) | 22 | <1 |

The articling system is discriminatory

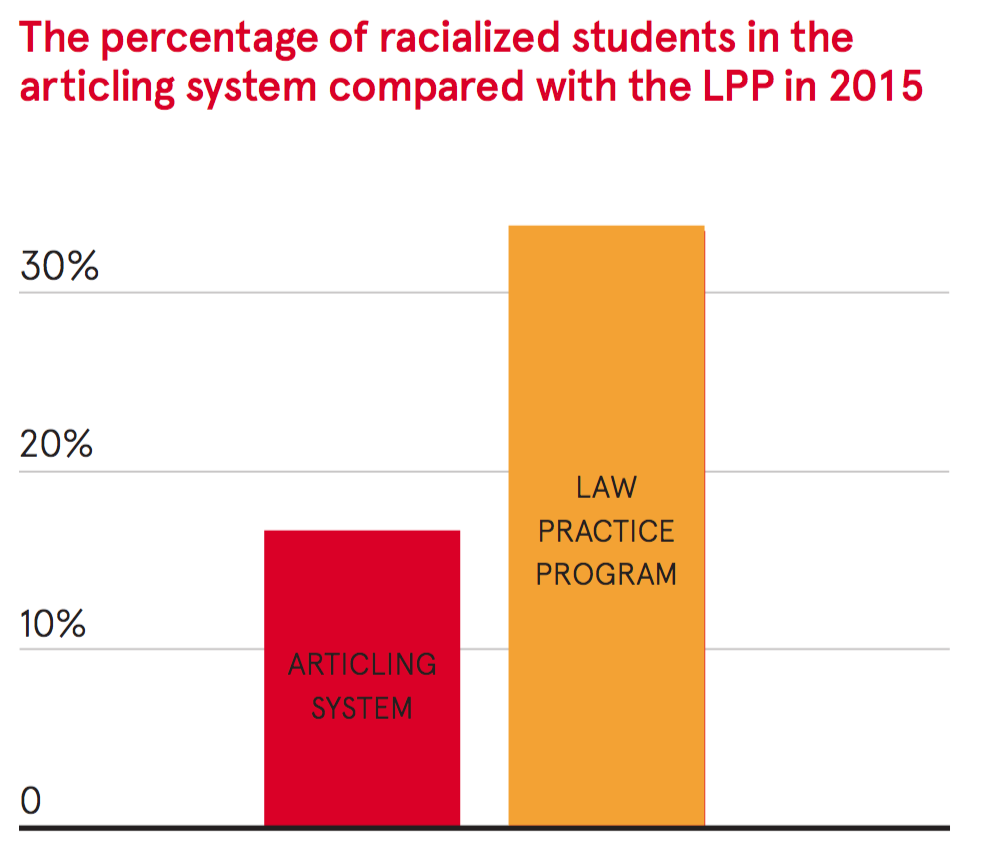

The cardinal rule of statistics is this: a single number means nothing on its own. So the fact that in 2015, as this chart shows, 18 percent of articling students self-identified as racialized might sound good. Now add this number to the mix: in that same period, 32 percent of LPP students were racialized. All of a sudden, 18 percent seems low.

The cardinal rule of statistics is this: a single number means nothing on its own. So the fact that in 2015, as this chart shows, 18 percent of articling students self-identified as racialized might sound good. Now add this number to the mix: in that same period, 32 percent of LPP students were racialized. All of a sudden, 18 percent seems low.

It’s hard to pin down what’s behind that racial divide. Is the problem outright racism? Has unconscious bias polluted the job market, making it more difficult for racialized law grads to land articling positions? In any case, one thing is clear: articling favours white students.

Articling doesn’t offer the best training

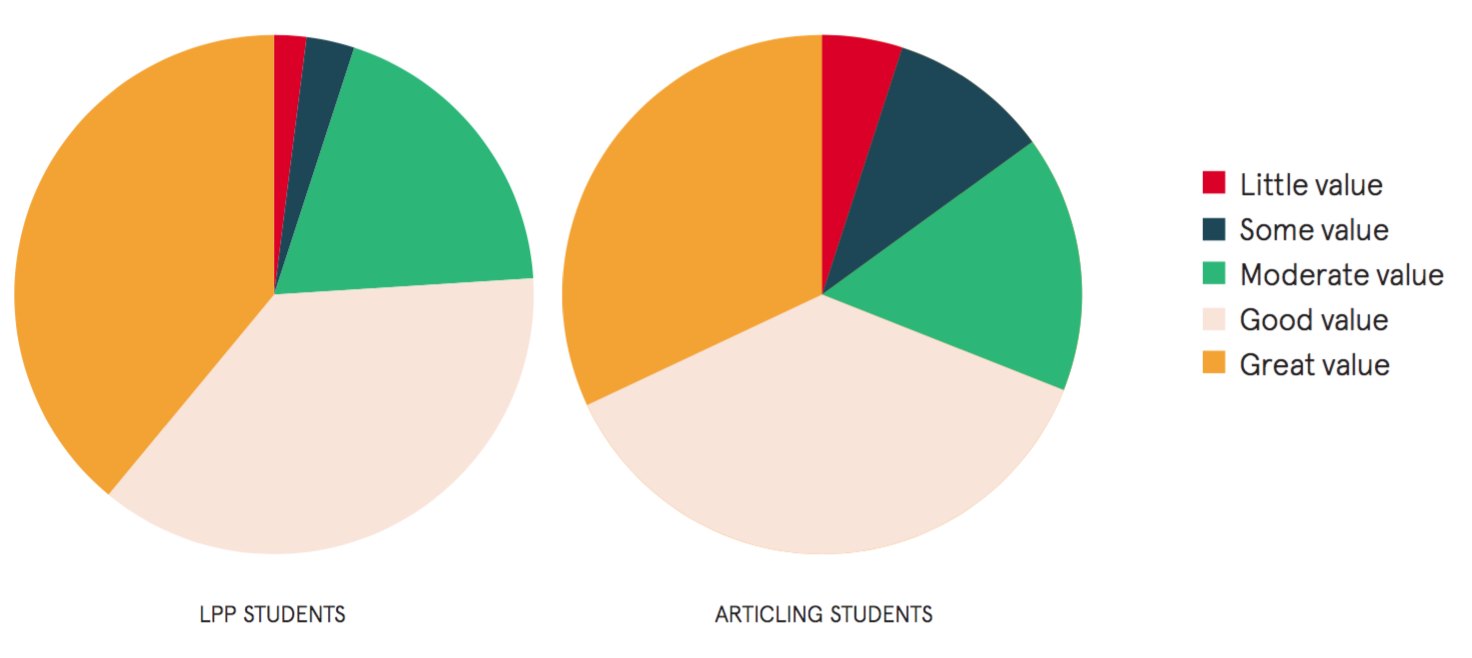

How many articling students applaud the training they receive? Well, in 2015, about 69 percent described their experience as either “good” or “great.” (The rest found articling to be of “moderate,” “some” or “little” value.) That’s pretty lousy. But it gets worse: among law grads who took the LPP the same year, that number rises to 76 percent. In other words, students who completed a brand new program were more satisfied than those who took part in a deeply entrenched system with decades of history and refinement.

A comparison of how students in the LPP and the articling system rated their post-law-school training in 2015:

This story is from our Winter 2016 issue.

This story is from our Winter 2016 issue.