“The role of the benchers is more important than it’s ever been,” declares Trevor Farrow, associate dean at Osgoode Hall Law School. In two years, he points out, the Law Practice Program (LPP) comes up for review. Meanwhile, benchers will debate whether to let non-lawyers invest in law firms, all while exploring how to encourage large firms to hire more women and visible minorities. At this moment, says Farrow, the profession needs more young, progressive voices leading the way.

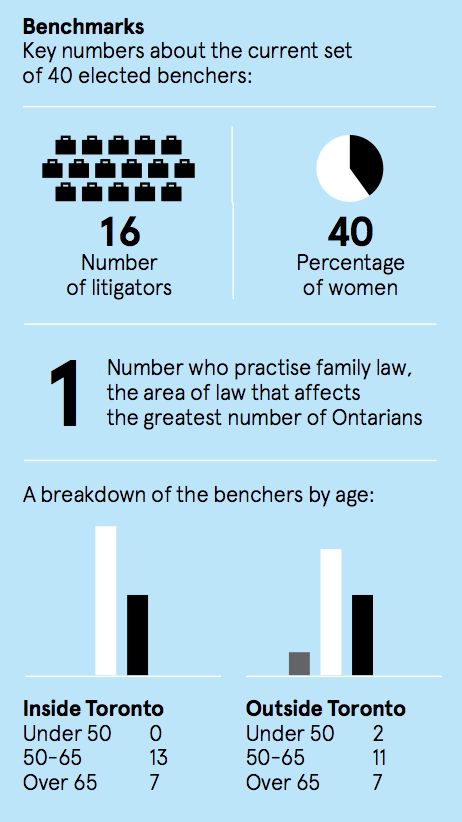

Today, out of the 40 elected benchers, only two are under the age of 50. It’s a statistic the Law Society of Upper Canada hopes will improve after the bencher election, which closes on April 30, says Janet Minor, treasurer of LSUC. “We’re going to get the best decisions in Convocation when we have the most diverse group of people.”

Today, the youngest bencher is Jacqueline Horvat, a 37-year-old lawyer at Sutts, Strosberg LLP in Windsor. After four years as a bencher, she respects her colleagues but believes the lack of young lawyers has affected the outcome of certain debates.

Today, the youngest bencher is Jacqueline Horvat, a 37-year-old lawyer at Sutts, Strosberg LLP in Windsor. After four years as a bencher, she respects her colleagues but believes the lack of young lawyers has affected the outcome of certain debates.

Horvat points to the 2013 decision to approve the LPP, which she voted against. As an alternative, she proposed, along with three other benchers, to abolish articling and replace it with a three-month course — an idea so radical, notes Horvat, that she “basically can’t say it out loud.” Still, in her view, it would ensure that all lawyers receive the same training. And it would allow every law grad to get licensed no matter what happens in the articling job market. “If there were more younger voices,” she says, “I suspect the LPP may have been defeated.”

Indeed, according to Morgan Sim, a second-year associate at Pinto Wray James LLP, many young lawyers support alternatives to articling. A common viewpoint, she says, is that the Law Society should encourage all law schools to adopt the curriculum of the law school at Lakehead University. At the northern school, students complete work placements in third year, and, as a result, don’t have to article before practising (they still have to pass the bar exam). Right now, too few benchers share that perspective. “I hope some young people throw their hat in the ring,” says Sim. “I’ll be an evangelist for them.”

Horvat is quick to point out she’s speculating about whether younger benchers would change the outcome of past votes. But she says that’s part of the problem: it’s impossible to know how young lawyers would vote until more of them win seats.

And that’s a tall order, says Horvat, for one big reason. Junior associates need support from the partnership at their firm. Partners must accept that, as a bencher, a lawyer will bill fewer hours and generate less revenue. When Horvat ran, in 2011, she was lucky: a partner at her firm, Harvey Strosberg, is a former Law Society treasurer. For him, making less money to support Horvat was a no-brainer. And he hopes other senior partners, when approached by an associate — or any lawyer — who wants to run, follow his lead. “It’s another aspect of pro bono,” says Strosberg. “It’s very important for the senior members of the bar to underwrite younger members of their firm.”

What the hell is a bencher?

Elected every four years, these 40 lawyers — 20 from inside Toronto, and 20 from outside — rule over the legal profession in Ontario. At a monthly meeting, called Convocation, they vote on policies that govern the profession. They sit on committees and preside over disciplinary hearings.

Bencher Paul Schabas says the job usually requires a commitment of five days a month, plus a lot of reading at home.

Despite what most lawyers think, benchers represent the public, not lawyers, says bencher Jacqueline Horvat. “Sometimes even the benchers lose sight of that.”

Read more of our 2015 Bencher Election coverage:

Joe Groia — the arch nemesis of the Law Society —

is running for bencher. Find out why

Bencher Janet Leiper launches a joint campaign with first-time

candidate Isfahan Merali to help promote a fresh legal voice

This story is from our Spring 2015 issue.

This story is from our Spring 2015 issue.

Illustration by Isabel Foo