We have always been a profession committed to ethics. Ethical issues involve a complex intersection, and indeed tension, between a lawyer’s obligations to a client, the court and the administration of justice. The profession’s focus on ethics has lately been overtaken by the cri de coeur of civility. Ten years ago, there was no public debate about the compelling need for civility in the bar. So what happened? Did we previously have an extraordinarily high tolerance for incivility? Have we been drinking some aggression-inducing Kool-Aid in the last few years, creating an epidemic of incivility? You don’t see any other professionals — dentists, doctors, engineers — having seminars about civility in their professions.

We have always been a profession committed to ethics. Ethical issues involve a complex intersection, and indeed tension, between a lawyer’s obligations to a client, the court and the administration of justice. The profession’s focus on ethics has lately been overtaken by the cri de coeur of civility. Ten years ago, there was no public debate about the compelling need for civility in the bar. So what happened? Did we previously have an extraordinarily high tolerance for incivility? Have we been drinking some aggression-inducing Kool-Aid in the last few years, creating an epidemic of incivility? You don’t see any other professionals — dentists, doctors, engineers — having seminars about civility in their professions.

There have been incidents of incivility that warrant attention. This is the behaviour at the extreme end of the scale — the lawyer throwing a cup of coffee at another lawyer, the lawyer swearing in court, the lawyer who is drunk at a client meeting. Really bad behaviour. Not merely a question of tone, a persistently unfounded legal argument or the odd intemperate comment.

But are we truly in the midst of an epidemic? Our governing bodies seem to think so: both here and in the U.S., professional governing bodies and courts are getting involved. This year, the Supreme Court of Canada in Doré v. Barreau du Québec adopted the definition of incivility as “potent displays of disrespect for the participants in the justice system, beyond mere rudeness or discourtesy.” Then the Law Society hearing panel in the Groia case imposed a higher standard, defining incivility as “a consistent pattern of rude, provocative or disruptive conduct by the lawyer, as well as ill-considered or uninformed criticism of the competence, conduct, advice or charges of another lawyer.”

Should the bar be set so high? Or do we need more confidence in our profession that most issues of civility will take care of themselves; that the door of the Law Society should not be the first stop? Only when bad conduct, rudeness and acrimony distracts from the real focus of the justice system, interferes with its proper functioning and undermines participation in and use of the justice system does it become a problem warranting the regulator’s attention.

Civility, however, plays an important role in the work of a lawyer. It has absolutely nothing to do with making us a kinder, gentler nation of lawyers. Nor does it have anything to do with convincing the public that we really are nice and polite. It is about this one essential fact: civility is integral to effective advocacy.

Your job as an advocate is to convey your message. If the court is not getting your point, it is because you have not found the right way to clearly present it. Your job, always, is to figure out how to be heard on behalf of your client. And it is hard to be heard above the din of incivility.

Civility as a part of effective advocacy is important as it grounds your credibility. Consider the boy who cried wolf. If you make allegations at the drop of a hat, if you are routinely rude, it soon becomes an old song and dance. You will lose credibility with your colleagues and with the court. If engaging in uncivil behaviour can ever be a “strategy,” then it is a poor one. You will be viewed as a person to be managed or ignored rather than listened to.

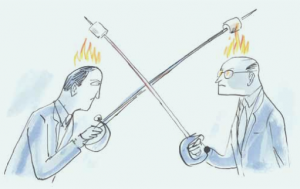

Every interaction with a colleague or a judge is advocacy. Effective advocacy requires control. A lack of civility displays a lack of control. Loss of control means that you are not functioning at your best.

While civility is an important aspect of advocacy, professionalism and credibility, it does not make you less of a fighter, less fearless or less vigorous an advocate. When Winston Churchill sent a letter to the Japanese ambassador announcing war upon Japan, he ended it with: “I have the honour to be, with high consideration, Sir, Your obedient servant.” When criticized, Churchill said this about his unfailing civility even in the midst of a war: “Some people did not like this ceremonial style. But after all, when you have to kill a man, it costs nothing to be polite.” Fight and vigorous advocacy are not anathema to civility.

Marie Henein is the founding partner of Henein and Associates.

Illustration by Graham Roumieu