Lawyers are by definition solvers of other people’s problems, so it’s no surprise if they dread becoming clients themselves. It’s one thing to turn to a colleague when buying a family home or writing a will. It’s quite another to require legal counsel when a lawyer’s reputation, his most valuable asset, is at stake. And there are but a select few lawyers in Canada whose skill, experience and — above all — discretion have made them the go-to for lawyers in crisis.

When problems arise, the objective is usually to keep things quiet — including the act of hiring a lawyer in the first place. So when David Cowling, a partner at Mathews, Dinsdale & Clark LLP, filed a defamation lawsuit in March 2010 against two junior associates at his own firm, it created a rare spectacle in the legal community.

In January 2009, Cowling and two unnamed partners were accused by junior associate Sarah Diebel of engaging in inappropriate behaviour — “rubbing their butts up against me and other women, putting their arms around me at any chance they got and flirting heavily” — at a firm-sponsored event. The story was later supported and added to by Adrian Jakibchuk, another associate at the firm. (Cowling vehemently denied the allegations and accused Diebel and Jakibchuk of malice in their complaints.)

An independent investigation followed. And then, nearly a full year later in March 2010, bombshell: Cowling filed a defamation suit claiming $2.3 million in damages against the two lawyers. The media pounced, everyone lawyered up and the legal community settled in to watch the fireworks.

The case, which is still at the pleadings stage, now features an impressive array of legal firepower. Cowling, who specializes in labour arbitration hearings and collective bargaining negotiations, retained Andrew Burns, a well-regarded civil litigator at Hunt Partners LLP, a Toronto boutique firm that specializes in reputational and legal risk. Burns left a large-firm partnership to join senior partner Doug Hunt, a former assistant deputy attorney general and director of criminal law for Ontario.

Diebel, who left Mathews Dinsdale in June 2009 and now practices law with the Ontario Power Authority, retained Beth Symes of Symes & Street. A co-author of the book Women and Legal Action, Symes is also one of the original founders of the Women’s Legal Education and Action Fund (LEAF) and a lifelong advocate of gender equity in the profession. Jakibchuk, who left the firm shortly after Cowling launched his suit and now practices with Sherrard Kuzz LLP, chose Paul Schabas, a partner at Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP and one of Canada’s preeminent defamation lawyers.

And Mathews Dinsdale, though not named in the suit, turned to Terry O’Sullivan of the highly regarded litigation boutique Lax O’Sullivan Scott Lisus LLP, which acts regularly in employment disputes and defamation actions.

Despite the attention Cowling’s case has garnered, O’Sullivan’s involvement went unreported. While O’Sullivan is known as one of the best civil and commercial litigators in Canada, his key role as fixer is one that he — and a small handful of others — quietly plays for many managing partners.

“I see a lot of interesting files,” says O’Sullivan, “and I cannot comment on any of them.” Chris Paliare of Paliare Roland Rosenberg Rothstein LLP echoes the sentiment: “My work for lawyers and law firms is not something I trumpet. It’s something I prefer to do under the radar.”

Ronald Slaght of Lenczner Slaght Royce Smith Griffin LLP, another lawyer’s lawyer, also declines to comment on his files: “If I did, it would likely be the first time people found out that I had anything to do with them.”

These lawyers, along with small group of others — including Paliare Roland partner Linda Rothstein — are the profession’s keepers of secrets and a first call for lawyers in trouble. They conduct internal investigations on allegations of sexual harassment, handle thorny negligence claims, settle acrimonious partnership disputes and defend their peers against charges of professional misconduct. They’ve helped keep many of the legal community’s skeletons locked firmly in the closet.

“We will often give files a name that obscures the people involved and the nature of the dispute,” says Slaght. Code names for personal meeting calendars and boardroom bookings are equally common. It is not unusual for only one or two members of the firm to know the details of a sensitive file.

In addition to being famously tight-lipped, O’Sullivan, Paliare and Slaght have a number of other things in common, which make them counsel of choice for lawyers in trouble. All are civil litigators approaching their 30th year at the bar. They are highly accomplished with well-deserved stellar reputations.

They are also successful pioneers in boutique litigation, whose primary line of business often lies in handling cases for large firms that need to resolve a conflict of interest.

Because the big firms’ key decision-makers already turn to them for help with their clients’ files, it’s not a stretch for them to seek advice on their own sticky situations as well. “If you’re a large firm, you don’t necessarily want advice from a competitor,” says Will McDowell, a former McCarthy Tétrault LLP litigator who served as associate deputy minister of justice of Canada before joining Lenczner Slaght. “It’s easier to approach a smaller firm.”

But it’s not only what they do that puts these three at the top of the lawyers’ lawyers list, it’s how they do it. “What you get from each of these guys is unvarnished advice,” says McDowell. “When people are in over their heads, these particular lawyers will immediately clear space in their day for them.

“They provide lots of free advice. And they all have the ability to form a judgment quickly. They can quickly tell you: here’s the worst-case scenario, here’s the most likely outcome and here’s what you need to do next.”

When lawyers are in need of counsel, it’s often the result of a chain of events spanning many months. Sometimes mistakes have been made along the way; sometimes a case simply becomes too complex for them to handle — something no one likes to admit. “They want someone who will not think badly of decisions made in the past and who won’t second-guess them,” Slaght says.

While these lawyers are mum about their work for others of their profession, sometimes publicity comes unbidden. In 2007, for instance, Paliare represented a client whose position and misdeeds were such a potent mix they inevitably captured the media’s interest. George Hunter was a former treasurer of the Law Society of Upper Canada whom the LSUC suspended for 60 days for professional misconduct after he admitted to engaging in a two-and-a-half-year affair with a client (known only as XY) while he represented her in a family law case. The Law Society had originally sought a longer suspension, but Paliare successfully argued that Hunter’s fall from grace was already a greater punishment than most lawyers would face.

O’Sullivan was also involved in a case that garnered substantial media attention. In its May 2010 edition, Toronto Life magazine put Diane LaCalamita on its cover and published a lengthy story about her allegations of gender discrimination against McCarthy Tétrault for failing on a verbal commitment to make her a partner. O’Sullivan, who represented McCarthys, received a lone mention in the story. It came in the second-last paragraph, describing him only as “a 60-something commercial litigator,” as though he were an afterthought.

Of course, neither he nor Paliare sought the publicity. Quite the opposite, in fact. According to Lisa Borsook, the managing partner at WeirFoulds LLP, the ability to “turn off the burner” on the publicity is a key skill for any lawyer’s lawyer. Media interest in LaCalamita’s case has fizzled since peaking with the Toronto Life article.

One senior Bay Street lawyer agrees that O’Sullivan handled the case extremely well. LaCalamita says she should have been made a partner. McCarthys disagrees. The parties will be fighting over her merits as a candidate for partnership, he said, “but given the publicity the case has drawn, that can’t be McCarthys defence.” Instead, the firm has to first buttress its credentials on equity and women’s issues in order to shift the focus back to the issue of LaCalamita’s suitability as a partner. “Terry has successfully done that, and the case is no longer drawing attention.”

Perhaps a similar attitude was behind Mathews Dinsdale’s choice of O’Sullivan. When Cowling filed his suit last year, the case made headlines in the Financial Post and on many legal blogs. Cowling, Diebel and Jakibchuk have all surely girded themselves for a public battle that could leave everyone’s reputation in tatters, regardless of who wins. But with O’Sullivan, Mathews Dinsdale has one of the few lawyers who might be able to put the lid back on Pandora’s box.

O’Sullivan, Paliare and Slaght all share a gift for cooling things down from a boil to a simmer. “When I need to seek outside counsel, I am always mindful of the publicity that a particular dispute will attend,” says Borsook. “There are certain lawyers who are publicity hounds — the players you read about in the papers. It’s unlikely they’ll ever be representing a law firm.” Such is the career of a fixer: universally respected within the profession, completely unknown to the public and happy to keep it that way.

This story is from our Spring 2011 Issue.

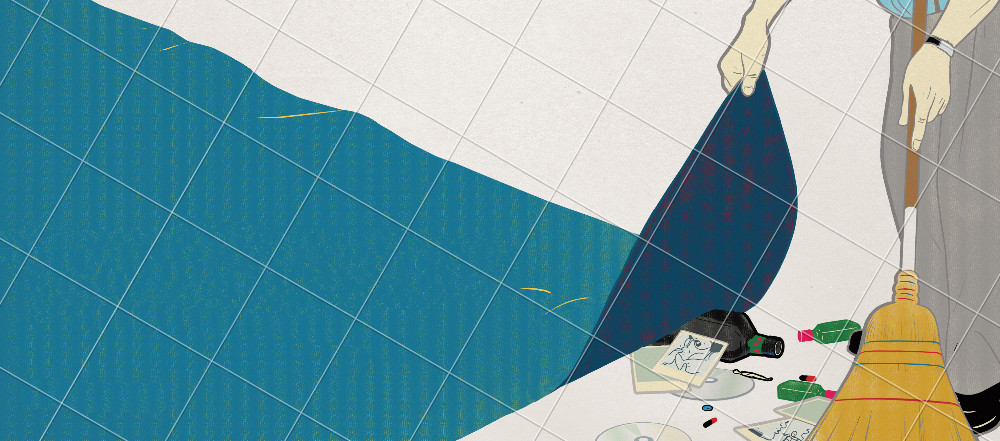

Illustration by Jason Schneider.