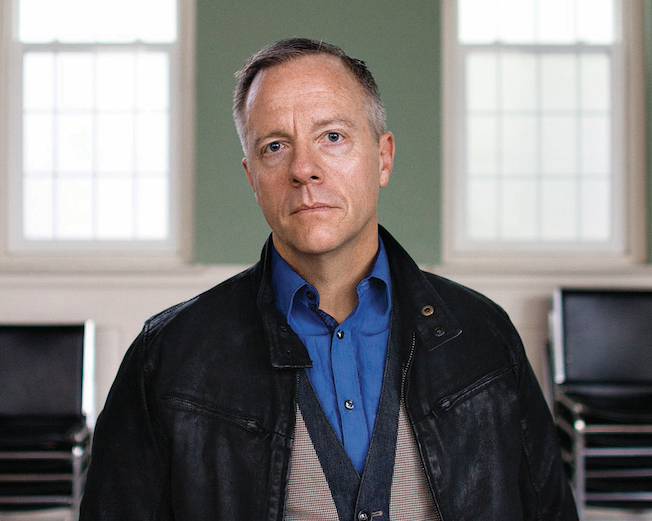

“Ihad no idea that innocent people were, every day, being treated like guilty people,” says Ontario’s former attorney general Michael Bryant. “I had no idea that the presumption of innocence is a joke.” It’s a brisk fall day, and we’re having lunch in the cafeteria at the largest courthouse in Brampton. Bryant, who turned 50 this year, is clean-shaven with short grey hair, his face framed by hipster-thick black glasses. In between bites of Caesar salad, Bryant laments how much he got wrong about Ontario’s justice system when he ran it from 2003 to 2007. But he’s starting to learn. And he’s appalled.

I’ve come to court to watch Bryant spend a day conducting bail hearings. For the past year, he’s done this a few times a week, using bail court as the staging ground for his long-term plan: to build a full-fledged criminal-law practice.

On such days, his job title is duty counsel. In return for a paycheque from Legal Aid Ontario, Bryant stands in bail court all day and represents people the police have charged, but who lack a lawyer to negotiate their release from custody. Sitting in the courtroom, I watch as police haul citizens up from the cells in the basement and plop them into a Plexiglas-encased witness box. Each person then meets Bryant, and the two chat for a couple minutes over the glass before the hearing starts. If anyone recognizes him as a former attorney general, they don’t show it.

Nor do they seem aware that Bryant was once charged with a serious crime himself. Bryant may in fact be most famous for his involvement, in 2009, in a car accident that left cyclist Darcy Allan Sheppard dead — and Bryant facing charges for dangerous driving causing death and criminal negligence causing death. (His lawyer, Marie Henein, built a defence so strong that the Crown dropped the charges before trial.) In court, Bryant looks anything but a criminal. He stands five foot eight, wears a grey textured suit with a matching vest, a crisp dress shirt, a bold red tie and brown leather shoes. He radiates the image of, well, a lawyer.

Bryant stands in the doorway of Sanctuary Ministries, a Christian charity that inspired him to practise criminal law on behalf of the poor

At lunch, our conversation turns to a particular hearing from the morning. Bryant had represented an 18-year-old who’d been in custody for 13 days without having a bail hearing. The day after police arrested him (for, allegedly, spitting on a woman’s face on a bus, running away and obstructing arrest) he arrived in court at 4:30 p.m. — and the justice of the peace refused to hear him at such a late hour. He did win bail eventually, but after a two-week delay.

“So he spent every night and weekend in prison at Maplehurst,” explains Bryant. “And during weekdays, he was in the basement of the courthouse, waiting. You can imagine that, by day 10, he says, ‘Okay, where do I sign? Get me outta here.’ That’s when you get the guilty pleas.”

Bryant seems well rested and is both enormously friendly and polite — in essence, playing the role of a politician making a journalist feel comfortable. He answers each question with care, though most prompt him to sound off at length on the ills of the justice system. “Once he pleads guilty, good luck getting a job.” Without work, Bryant adds, the teenager is more likely to turn to crime. “So he gets arrested again, but has a criminal record so it’s a lot harder to get out on bail. To get out of custody, he pleads guilty. The next thing you know, he’s in and out of jail and, basically, his life is over.”

To hear such language spring from the mouth of a former attorney general is striking. But it’s just as curious to see Bryant, who once presided over the justice system from the penthouse, now conducting bail hearings in the salt mines. “We’ve certainly noticed him,” says Edmond Brown, a criminal lawyer in Brampton. “I mean, he could be making a million dollars a year on Bay Street. So we’re all wondering, Why is he here?”

All of his life, Bryant had one overarching goal: to be a politician, just like his father, who served as the mayor of Esquimalt, B.C., when Bryant was a child. His pathway there, he knew, was through the law.

That dream brought Bryant to Toronto in 1989, where, first, he was a precocious law student: he graduated from Osgoode Hall Law School with the silver medal. He then clerked at the Supreme Court of Canada under Beverley McLachlin, now the chief justice. Next, he was a blue-chip grad student: he earned a master of laws at Harvard on a Fulbright Fellowship. In 1995, he landed on Bay Street at McCarthy Tétrault LLP in the litigation group. “I thought he was terrific,” recalls Tom Heintzman, Bryant’s mentor at McCarthys, who now runs his own mediation and arbitration firm. “He was always so enthusiastic and very upbeat. He made friends with everyone so easily.”

Bryant didn’t stay on Bay Street for long. After three years, he ran for provincial government under the Liberal banner. He won a seat, and spent four years in the official opposition. In 2003, when Dalton McGuinty and the Liberals sailed to a majority government, the new premier gave Bryant a plum cabinet position: at 37, Bryant became Ontario’s youngest-ever attorney general. He seemed immune to failure.

After four years at the top of the justice system, a difference of opinion with McGuinty led to demotions in the next two cabinet shuffles — first to Aboriginal affairs and next to the economic-development file. “I was still part of the group,” says Bryant. “I just wasn’t cool anymore.” In June 2009, Bryant left the legislature to serve as the CEO of Invest Toronto, a new agency that then-Mayor David Miller had set up to lure investment and job creators to the city. Bryant, though, still had political ambitions. “I thought I might do what some politicians do,” he recalls, “which is go into the private sector, or, in my case, work in economic development, and return to politics when there was a leadership race.”

But then the accident happened. In August 2009, Bryant and his wife, Susan Abramovitch, an entertainment lawyer at Gowling WLG, were celebrating their 12th anniversary. The couple was driving through Yorkville in their top-down Saab convertible. Bryant was at the wheel. What happened next has been the subject of meticulous media scrutiny, but the basic storyline, in Bryant’s telling, is this. At an intersection, Bryant encountered Darcy Allan Sheppard, who was on his bike and behaving erratically (drunk, shouting). Bryant tried to drive away but as he did he got close to Sheppard, who became angry. Sheppard shouted and reached inside the car. Bryant tried once more to drive away, knocking Sheppard against a fire hydrant. As Sheppard fell to the ground, he suffered a punishing blow to the head and later died in hospital.

Police arrived on the scene and swiftly arrested and charged Bryant. He then hired Marie Henein. Though she had spent her first 11 years practising with Eddie Greenspan (making named partner at his firm) and had run her own firm for seven years, this would be one of her most high-profile cases yet. In the coming months, Henein collected affadavits from a number of people who had seen Sheppard, on separate incidents, acting violently toward drivers on his bike. In a rare move, she disclosed this evidence to the Crown before trial, hoping the Crown’s legal team, Richard Peck and Mark Sandler, would drop the charges — which, after completing their own investigation, they did.

Bryant had escaped the clutches of the law, but he had changed. “Sometimes you have a life event and it’s a tragedy, and your ego gets hollowed out,” he says. Bryant scrapped his plans to run for premier. “Not because it became less realistic — although maybe it did, undoubtedly it did — but getting a big job and having a lot of power was no longer important to me.”

Over the next year, Bryant’s marriage collapsed. His brother died. And he grappled with PTSD from the accident.

For the first time, he had no grand plan.

While Bryant was fighting his charges, he had stepped down from Invest Toronto and, to pay the bills, worked at Ogilvy Renault (now Norton Rose Fulbright LLP). He stayed at the firm for two years, but left to take a job at Ishkonigan, a mediation firm run by Phil Fontaine, the former chief of the Assembly of First Nations. That job saw him fly around the country, helping to negotiate land-claim disputes. He also worked on a memoir. In 2012, Viking Books published 28 Seconds, a deeply self-critical account of his political career. Bryant lambastes, in chapter after chapter, the ego and arrogance that stoked his ambition. But the book also maintains that, though Sheppard’s death is a tragedy, it’s not the product of negligence on his part. (His lack of repentance drew resentment from Sheppard’s father.) Bryant was also busy as a father. He has two children — a daughter, now 14, and a son, now 12 — and shares custody of them with Abramovitch.

At Sanctuary, Bryant made friends in the drop-in room where the charity serves meals

In the main, though, Bryant remained adrift. He didn’t know how he wanted to spend the rest of his life.

But as he was grappling with the aftermath of the accident, he started spending time at the Sanctuary Ministries, a non-denominational Christian charity just south of Yorkville that helps people living on the street — by providing them with meals, employment assistance and a health clinic. The folks at Sanctuary had seen Bryant on the news and thought he needed help. So they invited him to come by for a visit. (They also paid greater attention to the story because Sheppard sometimes visited Sanctuary.) “We all realized that Michael had become a political pariah,” says Greg Paul, the founder and pastor at Sanctuary, who sometimes delivers the Sunday-evening service. “His marriage had fallen apart. His brother had died. Many people thought he’d gotten away with something because he was a person of power. All this added to up to a guy who was seriously isolated and badly battered — and those are our people.”

Bryant agreed to drop by. “The first few times, I sat by myself, didn’t know what to do, ate and then ran,” he recalls. But he kept coming back. “I’m still not sure why,” he says. “But slowly people come up to you, since they recognize you from before, and you start making friends.”

He soon became a regular. That he could make real connections with the homeless and impoverished was a surprise. Bryant had never had relationships with people on the street. It was deeply meaningful. Within a couple years, he had an idea about how to spend the rest of his life: he considered becoming a minister.

Bryant was never a habitual church-goer, nor was he all that fluent in Christian gospel. But he grew up “generically Protestant,” always believed in God and saw real value in religious belief. So the idea wasn’t entirely out of character.

He shared this thought with Paul, telling him, “I want to do what you do.” But the pastor thought it wasn’t the right fit. “I knew that if he went into the conventional ministry, he’d end up in a church somewhere and it would drive him crazy,” recalls Paul. “That’s not what he wanted.” What Bryant did want, Paul had gleaned, was to help the sort of people who frequented Sanctuary — the poor, the drug-addicted and everyone else who sits outside the borders of human regard.

Paul hatched a better plan. “I said, ‘You’re a lawyer! Be a lawyer! Look around the room here. There’s all kinds of guys who are before the courts who need a good person to stand on their behalf. That is gospel work, Michael! That’s what Jesus was talking about. That’s setting the captives free and opening the eyes of the blind.’”

Bryant loved the idea. “Greg told me to remember what Marie Henein did for me,” he recalls. “And he was right: to me, she was a rescue worker. She believed in me and fought for my innocence harder than anyone could, other than my family.” He resolved to become a criminal lawyer and build a practice that would serve those on the bottom rung of the socio-economic ladder.

His first instinct was to set up a small practice at Sanctuary, and primarily defend people there who need legal help and would pay him with Legal Aid certificates. But he soon realized that there weren’t enough potential clients to sustain a practice. So he had one option: to go out on his own.

In late 2015, Bryant started making moves. He launched a bare-bones website and spread the word to old colleagues who might send him work. Then he contacted Legal Aid Ontario to start working duty-counsel shifts.

Next, he needed an office. So he did what many junior sole practitioners do: he rented space at a chambers. He chose King Law Chambers, the sideline of criminal lawyer Sean Robichaud. Bryant picked the space, which is a few blocks east of Union Station, for its low cost and the promise of solid mentorship, which Robichaud was excited to provide. The two often chat about cases and Robichaud helps Bryant brainstorm courtroom strategies. “Michael has so much enthusiasm and idealism,” says Robichaud. “He seems born again.”

When Bryant’s term as attorney general ended, he had left his footprints on the criminal-justice system. For starters, he had a solid track record when it came to unclogging busy courts. When the courthouse at 393 University Avenue hit capacity, Bryant opened a new one at 330 University. He also overhauled the Ontario Human Rights Commission. In 2007, it took up to seven years for a human-rights complaint to work through the Commission’s bureaucratic machinery. Today, it takes roughly one year. Bryant also put more money into Ontario’s Drug Court, which provides court-supervised treatment to addicts charged with crimes related to their substance abuse — from trafficking to thefts they commit so they can afford more drugs.

But one event still leaves a sour taste in the mouths of defence lawyers: how Bryant reacted to Toronto’s “Year of the Gun” in 2005. Throughout his political career, Bryant touted himself as “tough on crime.” So his response to a year that saw 52 gun murders in Toronto — in the previous 10 years, the city averaged 30 gun homicides a year — was, not surprisingly, bare-knuckled. Bryant invested $100 million into, among other things, more prosecutors and a revamped forensic-investigation facility. “It was understandable from his position because it was a political response,” recalls Anthony Moustacalis, the president of the Criminal Lawyers’ Association, who now mentors Bryant. “But it was frustrating because there wasn’t a correlative increase in funding for Legal Aid.”

At the time, Bryant heard those voices of dissent. But he never gave them much credence. It was important to protect the public, he recalls thinking, so even if an innocent person gets “arrested and charged, they will get their due process.” Having spent a year on the front lines of the criminal courts, Bryant now sees fault in that logic.

Back at the Brampton courthouse, Bryant and I are standing in the hallway on a break. Bryant is high-energy, almost hyper. “It’s a bit of a rush,” he says of bail court’s fast pace.

I asked him if there is anything he now finds toxic about the justice system that didn’t bother him as attorney general. “Start with this: everyone I represent today is in cuffs. And they’re innocent. That’s wrong.” To cuff everyone, he says, strips them of their presumption of innocence. “And if you treat people like they’re guilty, they start to believe they’re guilty. That’s when they start thinking, Well, you know what, I’m sitting in cuffs. I’m in jail. I must have done something wrong. Then they plead guilty.”

When I call Marie Henein to chat about Bryant’s new career, I mention his gut-level aversion to the uniform handcuffing of his clients. “This is the sort of thing he wouldn’t have seen when working at a policy level, and that he would not have felt,” she says. “But once you’re sitting in court and you see someone brought in and their child is watching them shuffle along with their hands and legs shackled, you get a different perspective.”

Now that he’s working as a criminal lawyer, Bryant sees flaws in the system that he missed as the attorney general

Henein adds that she’s not surprised to see Bryant working in criminal law. During his own legal drama, she recalls, he had already begun to sympathize with the criminally accused like never before. “For the first time, he realized how extraordinarily powerless you feel in that process.”

Bryant heads back into court, and the proceedings hit a snag: an accused person’s file is missing. The clerks don’t have it; neither does the Crown. Bryant volunteers to check a different bail court, in case someone sent it there by mistake.

As Bryant darts out of the room, I follow him. He steps onto an escalator that leads to another courtroom on the second floor. “Thanks to that horrible attorney general Michael Bryant, we don’t have a digitized court system,” he quips. “So this is part of the job, chasing down paperwork.”

He walks into the other court, but the file isn’t there. The hearing will get pushed. “This is serious,” he says, as we head back down the escalator. “If we can’t get paper to go from one courtroom to the next — and we often can’t, because it’s paper! — then defendants don’t get heard. So what happens? They panic. They want to get out. They want their liberty. And they plead guilty.” (Two days later, I ask Bryant if the file turned up, and by then it had.)

It becomes clear that Bryant has developed one core critique of the court system: innocent people are pleading guilty. I ask Bryant how he can be so sure. Because, he replies, as duty counsel he often has to convince his clients not to plead guilty, even when he thinks they have a good shot at fighting the charges. “Out of the people who are denied bail, I’d say about two-thirds want to plead guilty,” he estimates.

There are no hard statistics on how often innocent people accept guilty pleas — it would be virtually impossible to track. But most academics take it as a given that this problem is widespread. As David Tanovich, a criminal-law professor at the University of Windsor, writes in a paper on the subject, close to 90 percent of criminal cases end with a guilty plea, so “it is only reasonable to assume that many innocent accused plead guilty to avoid the risk (or potentially increased period) of imprisonment or to avoid the barbaric conditions in some pre-trial detention centres.”

Bryant doesn’t blame this problem on any sole actor. “Anyone would be blown away by how dedicated the Crowns and court staff are,” he says. “The running around that gets done, chasing files — everyone works hard. Nobody is just going through the motions.” He pauses. “It’s actually a miracle the whole thing holds together.”

In fairness, Ontario’s current attorney general, Yasir Naqvi, wants to modernize the court. This fall, he proposed a battery of modest reforms, including putting dockets online and expanding the use of video-conferencing. But when a reporter with the Canadian Press asked him if Ontario’s courts would ever fully go paperless, he replied, “That’s really looking into the crystal ball and I won’t even try to answer that question.”

With the tech revolution on full display, such an answer may sound outrageous. But it’s important to critique the courts with a sense of history. For example, when I raise some of Bryant’s concerns with Edmond Brown, the Brampton-based criminal lawyer with 41 years of experience, he agrees with them, but quickly adds: “Over the years, things have gotten a lot better. Back when I started we didn’t even have the Charter. Judges are a lot better, too. We used to have these mean, wicked judges who would throw pencils at us. Everybody smoked; there were hardly any women. It was a different world. Today is better than that.”

Bryant has been sober for ten years. But for most of his adult life, he abused alcohol. He quit drinking in the middle of his term as attorney general, after years of working through hangovers and slurring his speech when he told his children bedtime stories.

He attends AA meetings, and still considers his sobriety a battle. Bryant says this helps him relate to his clients. The courts, he says, are swarming with addicts. The facts back up this claim: about 70 percent of federal prisoners have a substance-abuse problem. So when Bryant meets addicts in bail court, he often tells them his story. “I’ll go up to the box and say, ‘I’m in recovery, I’m an alcoholic and I’ve been sober for 10 years. You can make changes. You don’t have to do this for the rest of your life.’”

But the best he can do is suggest that they seek treatment: there is no way for a justice of the peace at bail court to help someone find a doctor and make sure they get help.

Two days after I shadow Bryant in Brampton, I visit him at his chambers. He steers me into a vacant boardroom. Before sitting down, he checks his phone. “Just give me one second,” he says. “I need to send a quick text to my kids.”

Bryant sits down and we soon start talking about how the courts deal with people struggling with substance abuse. A bail hearing from the day before is still on his mind. “I represented a man who was an alcoholic. He had gotten very angry and taken it all out on his wife,” he says. Bryant argued for his release. “I was saying, ‘If we get him sober, he will change as a person and it’s our best chance of stopping this violent behaviour.’”

The court denied him bail. No family member or friend had come forward as a surety, swearing to supervise him or make sure he would get help for alcoholism. Bryant understood the ruling. “The risk was too high,” he says.

But keeping the man in custody, adds Bryant, is also an imperfect solution. If a court found him guilty and sentenced him, he would still get out at some point — and he’d probably be worse off and more likely to reoffend. This would make society less safe. “This is the opposite of what the justice system is supposed to do.”

I ask what can be done. “We need to integrate, in a massive way, the health-care system into the courts,” he says. “We need to be able to release addicts into the custody of treatment centres and doctors. And we’re nowhere close to being able to do that.”

“Sometimes you have a life event and it’s a tragedy,” says Bryant, “and your ego gets hollowed out”

Is this a story of redemption? “People might assume that there’s some sort of expiation going on here, that Michael’s trying to work out his sense of guilt for what happened to Darcy,” says Greg Paul of Sanctuary. “But I don’t think that’s the motivation here. Really, it’s about finding meaning in his life. His experience with Darcy was part of that process, but I don’t think he’s doing what he’s doing out of guilt.”

It’s true, however, that Sheppard himself struggled with addiction, and was frequently tied up in the criminal-justice system. Bryant, in fact, thinks the courts failed to help Sheppard get treatment. He spends a chapter of his memoir on this subject.

So I asked Bryant if he was trying to help people, as a lawyer, that face the same problems Sheppard once did. “He was certainly part of a community for whom the criminal-justice system did nothing,” he says. “So it does occur to me that it looks like that. But that’s not conscious.”

Still, he will never shake the accident from his reputation. And not everyone agrees he’s innocent: an active blog, BryantWatch.wordpress.com, continues to publish pieces that suggest Bryant is more culpable than he is willing to admit.

“Today’s digital world is an extraordinary burden,” says Henein. “The mere fact of an accusation makes it extremely difficult for someone to move on. What’s the first thing you do when you meet someone? You google them. So for the rest of your life, you’re explaining yourself. It’s hard.”

Another skeptical view would be that Bryant is trying to rehab his public image. “I really don’t think this is some kind of stunt,” says Will McDowell, a litigator at Lenczner Slaght LLP, a former colleague of Bryant’s. (He worked at the Department of Justice when Bryant was attorney general, and alongside him at McCarthys.) “Some people might think he’s doing this to help his political career. But I just don’t think that’s true.” No matter what his motivation, adds McDowell, the work Bryant is doing is “a tangible contribution to the greater good.”

It’s even possible, depending on the cases he takes on, that Bryant’s new career could damage his image. Working as a criminal lawyer carries stigma of its own. “I’ve done many child sex-assault cases,” says Jessyca Greenwood, an eighth-year defence lawyer and a mentor to Bryant. “I’ll read the social media comments on the press coverage, and see people write, ‘I hope that the lawyer dies.’ I can tell you, this is not easy.” But she’s confident that Bryant could push through something like that. “In talking to him, I can tell he has a real passion for what he’s doing. And I think that’s partly because he can put himself in the shoes of the accused — and knows how bewildering, scary and humiliating the whole experience is.”

Near the end of my meeting with Bryant, I ask how he’s doing for money. “It’s never been tighter,” he says, noting that the rates Legal Aid Ontario pays for duty counsel (and certificates) are notoriously low, a concern that feels more real than it did when he was in a position to do something about it. “When I was attorney general, criminal lawyers would often complain that Legal Aid should pay higher rates,” he recalls. “I would say, ‘You’re asking me to give more money to lawyers?’ That never went over well.”

He now sees that Legal Aid truly needs more money — both to pay higher rates to lawyers (so they’ll stay in criminal law and be able to make ends meet) and so more people qualify for certificates. But he maintains that defence lawyers are bad at asking for more money. “When prosecutors ask for a funding increase, they say it’s in the name of increasing public safety,” says Bryant. But when the defence bar asks for more funding, they say the money is for defence lawyers. “What we should say is that the money will protect the right to a fair trial and the presumption of innocence.”

What are his plans for the near future? More of the same: shifts as duty counsel, and over time taking on more cases with a focus on the poor. “But it’s still early days,” he says. “So I’ll take whatever comes through the door.”