In the tech industry, the informal motto is “move fast and break things.” In law, the equivalent axiom might as well be “move slow and don’t touch anything.” The core tenets of our legal system are nearly 1,000 years old, and the norms and practices of the profession are similarly ancient. So what happens when an industry rooted in precedent—both legal and institutional—faces an unprecedented crisis?

We now have an answer to that question. In March, the COVID-19 pandemic turned the legal world upside down, shuttering offices, closing courthouses and making face-to-face client meetings impossible. What follows is the story of how three firms—an established personal-injury outfit, a brand-new workplace and alternative-dispute resolution practice, and one of the most storied litigation boutiques in the country—adapted to the biggest period of upheaval in a generation.

Part One: The response team

On the last Friday of February, Melissa Miller, a partner at the personal-injury firm Howie, Sacks & Henry LLP, went dancing with five of her colleagues. First, the group stopped at Mambo Lounge, a Cuban restaurant, for dinner and mojitos. Then, they headed to a nearby community centre for salsa and bachata classes. The vibe was surprisingly clubby: the lights had been dimmed, there was a DJ in a makeshift booth and a bartender mixed five-dollar rum and Cokes. “We were learning from the instructors but also from the people around us,” recalls Miller. “Every 15 seconds, I was dancing with somebody new.”

Today, such an event would be unthinkable. The advent of COVID-19 has forced society at large into an extended form of lockdown. That, in turn, has placed Howie, Sacks & Henry’s culture under enormous pressure. The tight-knit firm, with 12 partners and eight associates, has always valued camaraderie that cannot be sustained through water-cooler chitchat alone. The partners get most of their cases through referrals from lawyers and doctors, a strategy that requires them to keep a busy social calendar. Even lawyer-client relationships involve a high level of mutual rapport. Personal-injury plaintiffs must place immense trust in their legal representatives during a vulnerable phase in their lives. “There’s a human aspect to all of our cases,” says Valérie Lord, one of the firm’s associates.

In many respects, however, Howie, Sacks & Henry was prepared to weather the storm. Internal documents were stored electronically, clerks were already working from home several days a week and, because the business runs on contingency fees and settlement payouts, it didn’t rely on sending clients monthly or quarterly bills. Yet the partners were nervous. With the courts closed indefinitely, would they be able to reach settlements on any cases? And how could they maintain such an intensely personalized practice in a world on lockdown?

“G

et ready for business as unusual.” This was the advice that David Levy, the managing partner, delivered to staff on March 26, at the firm’s first virtual town hall. The style of work might change in the months to come, he explained, but the work itself would continue. The firm had no intention of laying anybody off.

During the previous week, Levy and Adam Wagman, a senior partner, had come up with a plan. The entire team would avoid the office, except a skeleton staff, who would show up twice a week to do such tasks as receiving documents and mailing out settlement cheques to clients. To increase cash flow, the partners would take 20-percent pay cuts. And, in the weeks to come, all lawyers on staff would focus on cases that could be advanced through remote work or virtual proceedings (such as pre-trial hearings and mediations). The message was clear: locking down didn’t mean slowing down. It just meant rejigging priorities.

But what about business development? Howie, Sacks & Henry gets most of its clients through networking. If a doctor or lawyer has a lead on a personal-injury case, the firm wants to get the call. This strategy requires a track record of high-quality work, but visibility doesn’t hurt either. That’s why the partners attend, on average, between 10 and 15 outreach events per month, including industry get-togethers — like meetings of the Advocates’ Society or Law Society — and informal hangouts with colleagues over, say, craft beer at King Taps, oysters at Buca or dim sum in Chinatown. “The business-development practice,” says Levy, “is as important as the practice itself.”

When the world shut down, the leadership team knew they’d have to get creative to maintain their marketing edge. In late March, Levy sent out personal emails to his closest contacts in the legal and medical professions. He discussed the difficulties of lockdown and invited recipients to share their stories. He was inundated with responses. The lines of communication were now open.

In April, Wagman was on an email exchange with a colleague at another firm, when suddenly he had an idea. “Let’s go for a bike ride,” he wrote. A few hours later, the pair hit the trail. They did loops around the Bridle Path, pedalled past Drake’s mansion and stopped at Goûter, a French bakery, for takeout pains au chocolat. It wasn’t Buca, but it was a good day’s networking all the same.

The firm works just as hard to maintain contact with its client roster. Seeking financial compensation, after all, is only a small part of the job. The legal team begins each case by asking: Does the client have the proper supports, like nurses, occupational therapists and counsellors? And is the insurance company covering these expenses? “The sooner a patient gets into rehabilitation, the more positive the health outcome will be,” says Levy. “This is where our work begins.”

In an era of social distancing, bespoke medical care has been difficult to provide. Wagman recently started representing a client who was in a car accident that left her with extensive injuries from head to toe. “I’ve never seen so many broken bones,” he says. Typically, such a patient would stay in a rehabilitation ward until she had reached an appropriate level of mobility. But, to free up beds for potential COVID-19 cases, the hospital discharged her within two months of the injury, before she had arrived at that point in her recovery. So Wagman found a physiotherapist willing to put on PPE and visit the client at home (once the Ontario government gave the green light for such care). To manage the stress of convalescence, he helped her set up regular video consultations with a social worker. And, to compensate for the absence of a live-in nurse, he arranged for her husband to get lessons in personal care. Most importantly, he made himself available 24/7 for phone calls.

The firm as a whole has exhibited the same dedication. “We’ve been meticulous about communicating with clients from the very beginning of lockdown,” says Lord. “If, before COVID, I depended mostly on emails, I’m now setting up calls and video chats. I want clients to hear—directly, in my voice—that, despite everything, I’m doing all I can to help them.”

If strong interpersonal relationships are key to advocacy and outreach, they’re also essential to office morale. The cases are emotionally tough. Howie, Sacks & Henry is currently representing, for instance, the families of Canadians who died on Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752, the passenger plane shot down over Iran. (The firm has been retained by 11 families in relation to 19 deaths.) The firm is also bringing claims against several nursing homes, including Orchard Villa, a long-term care facility that has seen one of the worst COVID-19 outbreaks in the province. These claims involve more than a dozen homes and about 50 clients. To handle this work with diligence and sensitivity, the team needs a bit of levity in what are otherwise difficult workweeks.

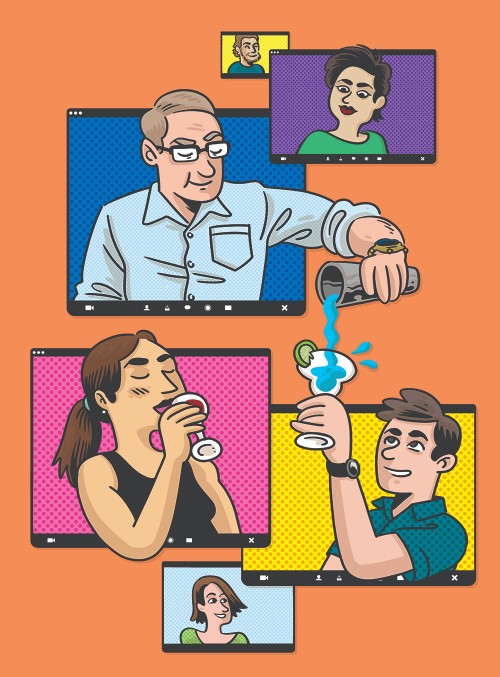

And so the firm has kept things fun. Each Friday, at cocktail hour, all the lawyers make a drink, alcoholic or otherwise, and then log on to Webex for bonding and banter. Maybe the associates will begin by ripping on one of their bosses for wearing goofy quarantine attire, or they’ll do a virtual tour of a colleague’s house. One time, Neil Sacks, a founding partner, picked up his guitar and regaled the team with old blues standards. (The rusticity of the music paired nicely with the ragged mutton chops he’d grown at home.) For the annual retreat, conducted virtually, the firm had a fun-in-the-sun theme, with everybody in beach hats and tropical shirts. “I was laughing so hard I couldn’t breathe in my snorkel goggles,” says Levy.

There’s been dancing, too. During the early stages of lockdown, Paul Miller, a partner, was quarantined with his kids when he saw them making TikTok videos. The resulting clip is hilarious: Miller’s 21-year-old daughter is in the kitchen getting down to Megan Thee Stallion’s viral hit “Savage,” when suddenly Miller appears, dancing awkwardly in the background. He sent the video to his colleagues, who found themselves laughing and cringing at the same time. One associate asked if, after lockdown, Miller might come to the next salsa and bachata class. His reply? “I don’t think I’m ready for that.”

Part Two: The incredible duo

On March 24, Morgan Sim, co-founder of the workplace and alternative-dispute resolution practice Parker Sim LLP, was having what felt like an unusually productive morning. Her husband, Nazorio Koné, an auditor with the French school boards of Ontario, had recently returned from abroad and was self-quarantining at their Toronto home. Sim and their two toddlers holed up at a friend’s farm near Prince Edward County. Her friend, another busy lawyer, was also at the farm with her young child. Which meant that there were three children in the house, all demanding food, play and entertainment.

Sim’s formal workday began at 8 p.m., once the kids were asleep, though she got through occasional emails and phone consultations during business hours. But March 24 felt different—at least, at first. She began her morning with a lengthy, uninterrupted phone call with her co-counsel on a case. The kids, meanwhile, were blessedly silent. In retrospect, she should’ve known something was up. When she emerged from her call, she discovered that “quiet playtime” was actually “take poop out of your diaper and smear it on the couch and rug time.”

There was shit everywhere. The adults went into emergency cleanup mode: Sim washed down the children, while her friend disinfected the rug and furniture. “Luckily, she had a dog,” says Sim, “so she had the appropriate cleaning products.”

The rest of the day was typically anarchic. At one point, the children sat around the dining table slamming their palms down and demanding yogurt—vanilla yogurt, to be exact. At another point, they ventured outside and came back covered in mud. Before the day was over, there had been a second diaper blowout. “By 4 p.m., we’d pretty much given up on parenting,” says Sim. “We parked the kids in front of the television and basically just called it a day.”

Meanwhile, her work life was blowing up. Once COVID-19 hit, many law firms faced the possibility of reduced clients and stagnant cash flow. Parker Sim had the opposite problem: nearly everyone in the business world suddenly needed workplace-law advice. Existing clients were calling with emergency requests, and the firm received at least two calls per day from potential new clients. To keep up, Sim worked seven days a week, as did her partner, Cenobar Parker, who was eight-and-a-half months pregnant with her second child. Amid the intensified pressures of family life, the duo had to steer their practice through an unprecedented national crisis. And one more thing: in March, Parker Sim was, itself, only three months old.

Parker and Sim first met as associates at Pinto Wray James LLP, the erstwhile employment-law firm on Bay Street. They were close from day one, and colleagues often joked that, one day, they’d start their own practice. In October of 2019, Sim had lunch with Parker, who’d gone solo a year earlier, and they discussed whether they could turn the old joke into reality. As it turns out, they could.

Parker Sim, which opened in January, offers a variety of workplace-related services. In a given week, they might advise an employer or employee on a contract negotiation, help an employee with disability benefits, litigate a human-rights claim or investigate a case of workplace misconduct. From the start, the clients came in fast. But nothing prepared the duo for the onslaught that would head their way in March.

The legal ground beneath everybody’s feet kept shifting. Consider, for instance, the thorny issue of layoffs. It’s well known that, in order to save themselves from going under, many business owners temporarily dismissed their staff. Less well known is that these kinds of layoffs may have been illegal: you can’t typically furlough your workforce unless your contracts allow you to do so. There had been speculation that, amid an emergency like the COVID-19 pandemic, those old rules may no longer apply, but that theory had not been tested in court. If employees started to sue their former bosses, it was impossible to predict how judges would rule.

The partners opted to embrace the uncertainty. They gave the best advice they could and were frank about what they didn’t (and couldn’t possibly) know. When advising employees who’d been laid off, they walked them through their options. Yes, they could sue for breach of contract, but such actions could jeopardize their hire-back prospects, and, on top of that, the laws might change. Similarly, when advising business owners who were contemplating layoffs, the duo helped them pick the best of the bad options. “We advised clients to be frank with employees to help them to understand the dilemma that the employers were facing,” says Parker. This honest, humane approach, she reasoned, would preserve goodwill and minimize the chances of legal repercussions.

The other big challenge was keeping up with the law. Seemingly each day, the government announced changes to its legislation on wage subsidies, employment insurance and other emergency benefits. To follow along, Parker and Sim turned to an unusual source: Twitter. Sim remembers the day Bill Morneau, the then-federal finance minister, announced changes to the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), a program designed to keep jobless citizens afloat. She needed to read the legislation ASAP, but it wasn’t easy to find. So she put out a Hail Mary tweet, hoping somebody with insider knowledge would chime in. A former law-school friend, who knew someone who worked in the Senate, saw the request and sent Sim a URL where the legislation would be posted. It was an abnormal way to source legal information, but these were abnormal times.

“It felt like we were living in a world of royal decrees,” says Sim. “Each morning, we’d wake up and watch Trudeau’s press conference in order to learn how the law would be changing.”

One month into the lockdown, some of the initial chaos subsided: employees started collecting benefits and employers figured out how to operate remotely or temporarily wind down their businesses. Eventually, the provincial government amended the Employment Standards Act, retroactively deeming COVID-related layoffs to be another category of temporary leave. This avoided a potential crisis for employers, who may have otherwise been found to have terminated those employees. On the whole, however, the legal landscape remains uncertain.

In early April, Parker gave birth to her son, Iliya. At the hospital, she kept up with clients by phone. “When you own your practice,” she says, “you can’t just shut down.” Once she returned home, however, her workload had let up, which allowed her to take a (partial) maternity leave. She still handled intake meetings with clients and some admin, but Sim covered most of the legal work.

Because daycares remained closed, Parker and her husband—Mayu Saravan, a director at BMO Capital Markets—found themselves taking full-time care of their three-year-old daughter, Naiya, along with their newborn. This challenge brought its share of pleasures. In between work emails and time with Iliya, Parker went on long walks with Naiya, during which they’d hunt for imaginary Easter eggs. “As a lawyer, I don’t often get to exercise that whimsical part of my brain,” she says.

Whenever Parker had important work to do, she’d plunk the toddler down in front of Cosmic Kids Yoga, the DayGlo-coloured YouTube series for children. At first, Naiya fell over every time she attempted the “tree pose” (balanced partly on one leg, arms stretched overhead). “Now,” says Parker, “she’s a balancing master.”

Despite the travails of the last few months, Parker and Sim believe that the pandemic might spur positive change within workplaces. For instance, they often represent employees seeking alternative work arrangements, perhaps because they have a disability or a childcare commitment. Bosses are sometimes hesitant to provide these accommodations, but the pandemic has shown that it is indeed possible for people to be productive outside of a traditional workplace. “We have always known that employees are not defined by their limitations,” explains Sim. “If they are allowed to make alternative work arrangements, they can be hugely valuable employees.”

Parker and Sim have also forged an incredibly strong partnership. If they can survive the pandemic, they can survive anything. Sure, the hours have been ungodly, and the work was often unorthodox. Yet they improvised, co-operated and, ultimately, made it through their first six months in business. Even if it was a (sometimes literal) shitshow.

Part Three: The league of legends

In 2018, Scott Hutchison, a founding partner of the litigation boutique Henein Hutchison LLP, was performing a cross-examination in one of the most high-profile cases in the country: the trial of David Livingston and Laura Miller, former aides to the premier of Ontario. Close to a decade earlier, the provincial government had halted construction on two gas-fired power plants, and the defendants were accused of illegally deleting digital files pertaining to that controversial (and costly) decision.

Hutchison—who represented Miller at the trial, but not Livingston—hoped to demonstrate that the expert witness in front of him, a computer forensics examiner and retired police officer, was too involved in the case to give unbiased evidence. Hutchison had roughly 40 documents, including memorandums and emails, showing that the witness had helped the police execute search warrants and had even suggested charges that the state might bring against the accused. That’s not how a neutral party behaves.

To make this point, Hutchison needed to present not just evidence but also a kind of story—in this case, about a witness gradually acknowledging that he wasn’t as impartial as he’d claimed to be. “I put each document in front of him and gauged his response,” says Hutchison. With every new file, the witness got visibly nervous. In such instances, says Hutchison, the witness will often look to the prosecutor or judge, as if seeking their help. In the end, the court accepted that the expert had too much skin in the game to give impartial testimony.

The cross-examination was successful, in part, because it happened live. Had it transpired remotely via videoconferencing or through written submissions, it wouldn’t have had the same effect. “Presenting evidence is not simply about downloading data into the court,” says Hutchison. “There’s a performative element to it.” A trial is a kind of human drama, with characters, dialogue, awkward silences and the occasional plot twist. (Miller was acquitted on all charges.)

One can make a similar point about the legal profession as a whole. Advocacy, after all, is an interpersonal endeavour. Clients and counsel build trust through face-to-face meetings. Lawyers come up with strategies via conversations with their colleagues. And cases are advanced through what Hutchison calls “informal advocacy”—the spontaneous dialogue that happens, for instance, in a hallway prior to a mediation.

Everybody at Henein Hutchison is attuned to the social nature of their work. The lawyers carefully stage-manage trials to make their arguments as compelling as possible. The two founders—Hutchison and his business partner, Marie Henein—have a firmwide open-door policy, whereby staff can drop by their offices anytime for in-person advice on a file. (The firm has three equity partners, three non-equity partners and 10 associates.) Even junior lawyers at the firm are highly sought-after among prospective clients; they may be relatively inexperienced, but they have unlimited access to two of the best legal minds in the country. When COVID-19 hit, the partners had to figure out how to preserve their workplace dynamic while all but shutting down the office. And they had to answer an even more pressing question: with the courts closed, what were they going to do about trials?

On Fridays at Henein Hutchison, once work wraps up, the employees often gather on the rooftop patio above the office for drinks and banter. After the first week of lockdown, the partners sent out wine and cheese to the home of each staff member and invited them to attend a virtual Zoom meeting instead. They spoke candidly about the challenges to come. Yes, these were unpredictable times, but the firm was committed to keeping all of its lawyers employed. There would be none of the nasty surprises—like out-of-the-blue pay cuts or layoffs announced over email—that people at some other firms had experienced.

To facilitate working from home, the partners expedited an initiative already underway to digitize the firm’s documents. They also cut office expenses, such as cleaning fees and work lunches. Each Wednesday morning, either Henein or Hutchison held remote office hours: anybody at the firm could pop into the Zoom meeting and seek advice on a case. “We used the technology as much as possible,” says Hutchison, “to replicate the open work culture we had before lockdown.”

And it went well, although lawyer-client dynamics still had their occasional awkward moments. Mark Strychar Bodnar, an associate at the firm, remembers lecturing a client, prior to a virtual mediation, on the importance of video-conferencing etiquette. The plan for the mediation was to have two communication channels: a Zoom meeting with everybody on it, as well as a separate meeting, where the client and counsel could speak privately while the proceedings were underway. “Be careful when making confidential statements,” Strychar-Bodnar warned. “Make sure the Zoom mute is on when you think it’s on.” About half an hour into the meeting, he moved into a private Zoom breakout room with the client and his co-counsel. While he was in this meeting, he answered a work call on his phone and forgot to mute his laptop. Luckily, he didn’t say anything confidential, but when he got back to his computer, the client and co-counsel were both laughing. “I had demonstrated exactly what not to do,” he says.

Pretty much everybody has stories like his. Since COVID-19 hit, we’ve all found ourselves fumbling with technology we rarely used before. In low-stakes situations, such hiccups hardly matter. But what about high-stakes proceedings, like a virtual trial? The concept has one clear advantage: if we take the courtroom online, it could promote greater access to justice by freeing up resources in our underfunded legal system. Hutchison worries, though, that virtual trials will undermine advocacy. “Under normal circumstances,” he says, “very few people would ever pick a video trial over a live one.”

Still, with the courts suspended and hopelessly backlogged, the alternative—waiting indefinitely, with your client in a state of legal limbo—is perhaps even less palatable. “In some cases,” Hutchison acknowledges, “a virtual trial is better than no trial.”

In June, Danielle Robitaille, a partner at Henein Hutchison, conducted Ontario’s first virtual criminal trial, after first getting consent from her client, the Crown and the judge. The preparations were at times surreal: at one point, the police brought a Bible to a witness who wanted to swear on the Good Book but didn’t own a copy. On the Monday when the trial was due to begin, Robitaille went to the office and put a sign outside the small boardroom telling colleagues to keep out. (The office was still open.) Inside the room, Robitaille had three monitors—one trained on the witness, one focused on everybody else and another with her documents and materials. When she needed a private word with her client, she met him in a virtual breakout room.

It was a unique experiment, with both benefits and drawbacks. “In virtual examinations,” she says, “you’re not walking around, so you don’t have a minute to catch your breath or think through your next line of questioning.” Still, she enjoyed being able to drink coffee on the job, an act that is normally verboten in court. That wasn’t the only liberty she took. “Although I was more tired at the end of the day than I usually would be,” she says, “my feet hurt much less. I wore running shoes throughout the entire trial.”

At Henein Hutchison, the staff misses the in-person office dynamic, but they have embraced Zoom as the next best thing. The lawyers still meet, virtually, each Friday, for an event now titled “Drinks on the Rooftop (but Not).” The conversations have been lively and playfully legalistic. A chat about the true-crime series Tiger King quickly progressed—or, if you prefer, devolved—into a debate over how the case would play out in Canada. (Although no consensus was reached, the lawyers posited that, under our country’s relatively tough animal-cruelty laws, the rival zookeepers would have been put out of business long before their feud reached its climax.)

A few weeks later, the lawyers had a Zoom debate about (you guessed it) the merits of making your own sourdough. Maya Borooah, an associate, recalls that the office was divided. In one camp were the pragmatists, like her, who insisted that homemade sourdough wasn’t worth the time. On the other side were the idealists. “They argued that the satisfaction of making the bread compensated for any deficiencies in taste,” says Borooah. She concedes that both sides had a point. True, some things in life really are more meaningful if you’re physically present for them. Then again, in a world of constraints, you can’t be dogmatic. Sometimes you have to settle for what’s most expedient.

This story is from our Fall 2020 Issue.

Illustrations by François Vigneault.